The Effects of Nuclear War

Chapter IV

CASE 2: A SOVIET ATTACK ON U.S. OIL REFINERIES

This case is representative of a kind of nuclear attack that, as far as we know, has not been studied elsewhere in recent years–a “limited” attack on economic targets. This section investigates what might happen if the Soviet Union attempted to inflict as much economic damage as possible with an attack limited to 10 SNDVs, in this case 10 SS-18 ICBMs carrying multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles (MlRVs). An OTA contractor designed such an attack, operating on instructions to limit the attack to 10 missiles, to create hypothetical economic damage that would take a very long time to repair, and to design the attack without any effort either to maximize or to minimize human casualties. (The contractor’s report is available separately.) The Department of Defense then calculated the immediate results of this hypothetical attack, using the same data base, methodology, and assumptions as they use for their own studies. *

Given the limitation of 10 ICBMs, the most vulnerable element of the U.S. economy was judged to be the energy supply system. As table 6 indicates, the number of components in the U.S. energy system forces the selection of a system subset that is critical, vulnerable to a small attack, and would require a long time to repair or replace.

OTA and the contractor jointly determined that petroleum refining facilities most nearly met these criteria. The United States has about 300 major refineries. Moreover, refineries are relatively vulnerable to damage from nuclear blasts. The key production components are the distillation units, cracking units, cooling towers, power house, and boiler plant. Fractionating towers, the most vulnerable components of the distillation and cracking units, collapse and overturn at relatively low winds and overpressures. Storage tanks can be lifted from their foundations by similar effects, suffering severe damage and loss of contents and raising the probabilities of secondary fires and explosions.

MlRVed missiles are used to maximize damage per missile. The attack uses eight l-megaton (Mt) warheads on each of 10 SS-18 ICBMs, which is believed to be a reasonable choice given the hypothetical objective of the attack. Like all MIRVed missiles, the SS-18 has limitations of “footprint” –the area within which the warheads from a single missile can be aimed. Thus, the Soviets could strike not any 80 refineries but only 8 targets in each of 10 footprints of roughly 125,000 mi2 [32,375,000 hectares], The SS-18’s footprint size, and the tendency of U.S. refineries to be located in clusters near major cities, however, make the SS-18 appropriate. The footprints are shown in figure 13. Table 7 lists U.S. refineries by capacity; and table 8 lists the percentage of U.S. refining capacity destroyed for each footprint.

Table 6. -Energy Production and Distribution Components

| Category | Prime sources | Numbers | Processing | Numbers | Distribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oil | Wells | Thousands | Refineries | Tens / hundreds (tend to be clustered) | Pipelines / rail / truck / barge / ship |

| Ports (imports) | Tens | ||||

| Pipelines (imports) | |||||

| Gas | Wells | Thousands | Gas plants | Tens / hundreds | Pipelines / rail / truck / barge / ship |

| Oil refineries | Hundreds | Deliquification plants | Tens | ||

| Ports (imports) | Tens | ||||

| Pipelines (imports) | Tens | ||||

| Coal | Mines | Hundreds | Usually at mines | Hundreds | Rail / truck / barge / coal slurry pipelines |

| Electric power production | Hydroelectric | Tens | Same as prime source | Powerlines / power grids | |

| Thermal | Hundreds | ||||

| Nuclear power | Tens | ||||

| Power grids (imports) | Unit |

SOURCES: Vulnerability of Total Petroleum Systems (Washington, D.C.: Department of the Interior, Office of Oil and Gas), May 1973, prepared for the Defense Civil Preparedness Agency.

National Energy Outlook: 1976 (Washington, D.C.: Federal Energy Administration), February 1976

The attack uses eighty 1-Mt weapons; it strikes the 77 refineries having the largest capacity, and uses the 3 remaining warheads as second weapons on the largest refineries in the appropriate missile footprints, In performing these calculations, each weapon that detonates over a refinery is assumed to destroy its target. This assumption is reasonable in view of the vulnerability of refineries and the fact that a 1-Mt weapon produces 5-psi overpressure out to about 4.3 miles [6.9 km]. Thus, damage to refineries is mainly a function of numbers of weapons, not their yield or accuracy; collateral damage, however, is affected by all three factors. it is also assumed that every warhead detonates over its target. In the real world, some weapons would not explode or would be off course. The Soviets could, however, compensate for failures of launch vehicles by readying more than 10 ICBMs for the attack and programming missiles to replace any failures in the initial 10. Finally, all weapons are assumed detonated at an altitude that would maximize the area receiving an overpressure of at least 5 psi. This overpressure was selected as reasonable to destroy refineries. Consequences of using ground bursts are noted where relevant.

The First Hour: Immediate Effects

The attack succeeds. The 80 weapons destroy 64 percent of U.S. petroleum refining capacity.

The attack causes much collateral (i. e., unintended) damage. Its only goal was to maximize economic recovery time. While it does not seek to kill people, it does not seek to avoid doing so. Because of the high-yield weapons and the proximity of the refineries to large cities, the attack kills over 5 million people if all weapons are air burst. Because no fireball would touch the ground, this attack would produce little fallout. If all weapons were ground burst, 2,883,000 fatalities and 312,000 fallout fatalities are calculated for a total of 3,195,000. Table 8 lists fatalities by footprint.

The Defense Civil Preparedness Agency (DC PA) provided fatality estimates for this attack. DCPA used the following assumptions regarding the protective postures of the population in its calculations:

- Ten percent of the population in large cities (above 50,000) spontaneously evacuated beforehand due to rising tensions and crisis development;

- Home basements are used as fallout shelters as are such public shelters as subways;

- People are distributed among fallout shelters of varying protection in proportion to the number of shelter spaces at each level of protection rather than occupying the best spaces first;

- >The remaining people are in buildings that offer the same blast protection as a single story home (2 to 3 psi); radiation protection factors were commensurate with the type of structures occupied.

These assumptions affect the results for reasons noted in chapter III. Other uncertainties affect the casualties and damage. These include fires, panic, inaccurate reentry vehicles (RVs) detonating away from intended targets, time of day, season, local weather, etc. Such uncertainties were not incorporated into the calculations, but have consequences noted in chapters II and III.

Table 7. -U.S. Refinery Locations and Refining Capacity by Rank

| Rank order | Location | Percent capacity | Cumulative percent capacity |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Baytown, Tex. | 3.6 | 3.6 |

| 2 | Baton Rouge, La. | 2.9 | 6.4 |

| 3 | El Segundo, Calif | 2.3 | 8.7 |

| 4 | Whiting, Ind. | 2.1 | 10.8 |

| 5 | Port Arthur. Tex | 2.1 | 12.9 |

| 6 | Richmond, Calif | 2.0 | 14.9 |

| 7 | Texas City, Tex. | 2.0 | 16.9 |

| 8 | Beaumont. Tex. | 1.9 | 18.8 |

| 9 | Port Arthur. Tex | 1.9 | 20.7 |

| 10 | Houston, Tex. | 1.8 | 22.5 |

| 11 | Linden. N. J | 1.6 | 24.1 |

| 12 | Deer Park. Tex. | 1.6 | 25.7 |

| 13 | Wood River, Ill. | 1.5 | 27.3 |

| 14 | Pasagoula, Miss. | 1.6 | 28.9 |

| 15 | Norco. La. | 1.3 | 30.1 |

| 16 | Philadelphia, Pa. | 1.2 | 31.3 |

| 17 | Garyville, La. | 1.1 | 32.4 |

| 18 | Belle Chasse, La. | 1.1 | 33.5 |

| 19 | Robinson. Tex | 1.1 | 34.6 |

| 20 | Corpus Christi, Tex. | 1.0 | 35.7 |

| 21 | Philadelphia, Pa. | 1.0 | 36.7 |

| 22 | Joliett. Ill. | 1.0 | 37.7 |

| 23 | Carson. Calif. | 1.0 | 38.7 |

| 24 | Lima. Ohio. | 0.9 | 39.6 |

| 25 | Perth Amboy, N.J. | 0.9 | 40.6 |

| 26 | Marcus Hook. Pa. | 0.9 | 41.5 |

| 27 | Marcus Hook. Pa. | 0.9 | 42.4 |

| 28 | Corpus Christi, Tex. | 0.9 | 43.3 |

| 29 | Lemont. Tex. | 0.8 | 44.1 |

| 30 | Convent. La. | 0.8 | 44.9 |

| 31 | Delaware City, Del. | 0.8 | 45.7 |

| 32 | Cattletsburg, Ky. | 0.8 | 46.5 |

| 33 | Ponca Citv. Okla | 0.7 | 47.2 |

| 34 | Avon, Calif. | 0.7 | 47.9 |

| 35 | Toledo, Ohio | 0.7 | 48.6 |

| 36 | Corpus Christi, Tex. | 0.7 | 49.3 |

| 37 | Torrence, Calif. | 0.7 | 50.0 |

| 38 | Nederland. Tex. | 0.7 | 50.6 |

| 39 | Toledo. Ohio | 0.7 | 51.3 |

| 40 | Port Arthur. Tex. | 0.6 | 51.9 |

| 41 | Wilmington, Calif. | 0.6 | 52.5 |

| 42 | Sugar Creek, Mo. | 0.6 | 53.1 |

| 43 | Ferndale. Wash. | 0.6 | 53.7 |

| 44 | Sweeny, Tex. | 0.6 | 54.3 |

| 45 | Borger, Tex. | 0.6 | 54.9 |

| 46 | Paulsboro. N.J. | 0.5 | 55.4 |

| 47 | Wood River. Ill | 0.5 | 55.9 |

| 48 | Benicia. Calif. | 0.5 | 56.5 |

| 49 | Wilmington, Calif. | 0.5 | 57.0 |

| 50 | Martinez. Calif. | 0.5 | 57.5 |

| 51 | Anacortes. Wash. | 0.5 | 58.0 |

| 52 | Kansas City, Kans. | 0.5 | 58.5 |

| 53 | Tulsa. Okla. | 0.5 | 59.0 |

| 54 | Westville, N.J | 0.5 | 59.5 |

| 55 | West Lake, La. | 0.5 | 60.0 |

| 56 | Lawrenceville, | 0.5 | 60.4 |

| 57 | Eldorado. Kans. | 0.5 | 60.9 |

| 58 | Meraux. La. | 0.4 | 61.3 |

| 59 | El Paso, Tex. | 0.4 | 61.7 |

| 60 | Wilmington, Calif. | 0.4 | 62.2 |

| 61 | Virgin Islands/Guam a | 4.1 | 66.3 |

| 62 | Puerto Rico a | 1.6 | 67.9 |

| 63 | Alaska a | 0.5 | 68.4 |

| 64 | Hawaii a b | 0.3 | 68.7 |

| 65 | Other c | 31.3 | 100.0 |

a Sum of all refineries in the indicated geographic area.

b Foreign trade zone only.

c Includes summary data from all refineries with capacity less than 75,000 bbl/day. 224 refineries included

SOURCE: National Petroleum Refiners Association.

Table 8. -Summary of U.S.S.R. Attack on the United States

| Footprint number | Geographic area | EMTa | Percent national refining capacity | Percent national storage capacity | Air burst prompt fatalities (x1,000) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Texas | 8.0 | 14.9 | NAb | 472 |

| 2 | Indiana, Illinois, Ohio. | 8.0 | 8 1 | NA | 365 |

| 3 | New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware. | 8.0 | 7.9 | NA | 845 |

| 4 | California. | 8.0 | 7.8 | NA | 1,252 |

| 5 | Louisiana, Texas, Mississippi | 8.0 | 7.5 | NA | 377 |

| 6 | Texas | 8.0 | 4.5 | NA | 377 |

| 7 | Illinois, Indiana, Michigan | 8.0 | 3.6 | NA | 484 |

| 8 | Louisiana. | 8.0 | 3.6 | NA | 278 |

| 9 | Oklahoma, Kansas. | 8.0 | 3.3 | NA | 365 |

| 10 | California | 8.0 | 2.5 | NA | 357 |

| Totals | 80.0 | 63.7 | NA | 5,031 |

a EMT = Equivalent megatons.

bNA = Not applicable.

The attack also causes much collateral economic damage. Because many U.S. refineries are located near cities and because the Soviets are assumed to use relatively large weapons, the attack would destroy many buildings and other structures typical of any large city. The attack would also destroy many economic facilities associated with refineries, such as railroads, pipelines, and petroleum storage tanks. While the attack would leave many U.S. ports unscathed, it would damage many that are equipped to handle oil, greatly reducing U.S. petroleum importing capability. Similarly, many petrochemical plants use feedstocks from refineries, so most plants producing complex petrochemicals are located near refineries; indeed, 60 percent of petrochemicals produced in the United States are made in Texas gulf coast plants.1 Many of these plants would be destroyed by the attack, and many of the rest would be for lack of feed stocks. In sum, the attack aimed only at refineries would cause much damage to the entire petroleum industry, and to other assets as well.

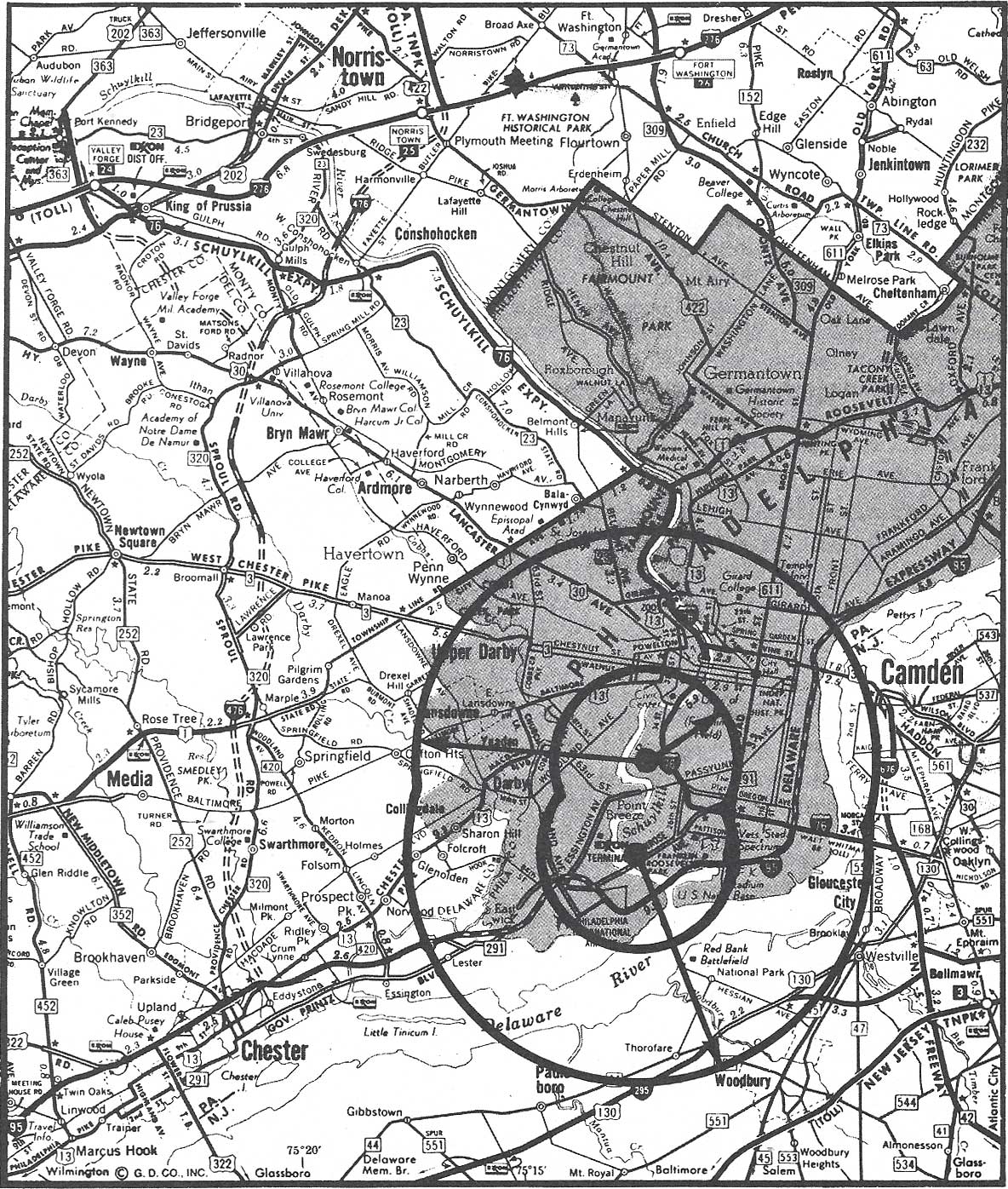

All economic damage was not calculated from this attack, because no existing data base would support reasonably accurate calculations. Instead, the issue is approached by using Philadelphia to illustrate the effects of the attack on large cities. Philadelphia contains two major refineries that supply much of the Northeast corridor’s refined petroleum. In the attack, each was struck with a 1-Mt weapon. For reference, figure 14 is a map of Philadelphia. Since other major U.S. cities are near targeted refineries, similar damage could be expected for Houston, Los Angeles, and Chicago.

Fatalities and Injuries

The Defense Civil Preparedness Agency (DCPA) provided not only the number of people killed within each of the 2-minute grid cells in the Philadelphia region but also the original number of people within each cell. These results are summarized in the following table for distances of 2 and 5 miles [3 and 8 km] from the detonations:

Deaths From Philadelphia Attack

| Distance from detonation | Original population | Number killed | Percent killed |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 mi. | 155,000 | 135,000 | 87 |

| 5 mi. | 5,785,000 | 410.000 | 52 |

Detailed examination of the large-scale map also indicates the magnitude of the problems and the resources available to cope with them. These are briefly discussed by category.

Petroleum

Local production, storage, and distribution of petroleum are destroyed. 1 n addition to the two refineries, nearly all of the oil storage tanks are in the immediate target area. Presumably, reserve supplies can be brought to Philadelphia from other areas unless– as is likely– they are also attacked. While early overland shipment by rail or tank truck into north and northeast Philadelphia should be possible, water transport up the Delaware River may not be. This busy, narrow channel passes within about 1.3 miles [2.1 km] of one of the targets and could become blocked at least temporarily by a grounded heavily laden iron ore ship (bound upriver for the Fairless Works) or by sunken ships or barges.

Electric Power

There are four major electric power plants in or near Philadelphia. Table 9 summarizes capacity, average usage (1976), and expected damage to these four installations.

Table 9. -Electric Powerplants in Philadelphia

| Name | Capacity (kW) | Average usage kW (1976) | Distance from blast | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schuylkill | 249,000 steam + 36,750 internal combustion (I.C.) | 111,630 | 1.3 | Electrical equipment destroyed Plant heavily damaged. |

| Southwark | 356,000 steam + 66,750 I.C. | 71.605 | 2.6 | Electrical equipment damaged or destroyed. Plant moderately damaged. |

| Delaware | 250,000 steam + 68,750 I.C | 162,799 | 4.9 | Electrical equipment moderately damaged. Plant intact. |

| Richmond | 275,000 steam + 63,400 I.C | 29,247 | 6.6 | Probably undamaged. |

| Totals | 1.130,000 kW (steam) + 235.650 I.C | 375,281 |

SOURCE: Electrical World: Directory of Electricial Utilities (New York. N.V.: McGraw Hill Inc. 1977).

While the usage figures in table 9 are average and do not reflect peak demand, it should be noted that a large percentage of this demand will disappear with destruction of the industrial areas along the Schuylkill River and of a large portion of the downtown business district. Thus, the plant in the Richmond section of Philadelphia, Pa., may be able to handle the emergency load. Assuming early recovery of the Delaware plant, there probably will be adequate emergency electric power for the surviving portion of the d distribution system.

Transportation

Air.– The major facilities of the Philadelphia International Airport are located about 1.5 nautical miles [2.8 km] from the nearest burst. These can be assumed to be severely damaged. The runways are 1.5 to 2.5 nautical miles [2.8 to 4.6 km] from the nearest burst and should experience Little or no long-term damage. Alternate airfields in the northeast and near Camden, N. J., should be unaffected./p>

Rail.– The main Conrail lines from Washington to New York and New England pass about a mile from the nearest burst. It can be expected that these will be sufficiently damaged to cause at least short-term interruption. Local rail connections to the port area pass within a few hundred yards of one of the refineries. This service suffers long-term disruption. An important consequence is the loss of rail connections to the massive food distribution center and the produce terminal in the southeast corner of the city.

Road.– Several major northeast-southwest highways are severed at the refineries and at bridge crossings over the Schuylkill River. While this poses serious problems for the immediate area, there are alternate routes through New Jersey and via the western suburbs of the city.

Ship.– Barring the possible blockage of the channel by grounded or sunken ships in the narrow reach near the naval shipyard, ship traffic to and from the port should experience only short-term interruption.

Casualty Handling

Perhaps the most serious immediate and continuing problem is the destruction of many of Philadelphia’s hospitals. Hospitals, assuming a typical construction of muItistory steel or reinforced concrete, would have a 5O-percent probability of destruction at about 2.13 miles (1 .85 nautical miles [3.4 km]). A detailed 1967 map indicates eight major hospitals within this area; all are destroyed or severely damaged. Another nine hospitals are located from 2 to 3 miles [3 to 4 km] from the refineries. While most of the injured would be in this area, their access to these hospitals would be curtailed by rubble, fire, and so on. Thus, most of the seriously injured would have to be taken to more distant hospitals in north and northeast Philadelphia, which would quickly become overtaxed.

Military

Two important military facilities are located near the intended targets. The Defense Supply Agency complex is located within 0.5 miles [0.8 km] of one of the refineries and is completely destroyed. The U.S. Naval Shipyard is 1.0 to 1.8 miles [1.6 to 2.9 km] from the nearest target and can be expected to suffer severe damage. The large drydocks in this shipyard are within a mile of the refinery.

Other

Several educational, cultural, and historical facilities are in or near the area of heavy destruction. These include Independence Hall, the University of Pennsylvania, Drexel Institute of Technology, Philadelphia Museum of Art, City Hall, the Convention Hall and Civic Center, Veterans Stadium, Kennedy Stadium, and the Spectrum.

* The Office of Technology Assessment wishes to thank the Defense Civil Preparedness Agency for their timely and responsive help in calculations related to this case, the Command and Control Technical Center performed similar calculations regarding a similar U.S. attack on the Soviet Union

- Bill Curry , “Gulf Plants Combed for Carcinogens." Wash/ngton Post, Feb 19, 1979, page A3