Los Alamos: Beginning of an Era 1943-1945

Living at Los Alamos

The fate of the Pajarito Plateau was sealed on November 25, 1942 in an Army memo to the Commanding General of Services of Supply.

“There is a military necessity for the acquisition of this land” at Los Alamos, New Mexico, the memo said, for use as a “demolition range.” The site included “approximately 54,000 acres” of which all but 8900 acres was public land supervised by the Forest Service. The Army estimated the cost of acquisition would be approximately $440,000.

Ranch School property included 27 houses, dormitories and other living quarters and 27 miscellaneous buildings valued by the Army at $246,000. By the time the school had been notified nearly two weeks later, it had already become clear that the original estimated Project requirement of 30 scientists was ill-considered and that the Ranch School’s 27 houses would be far from adequate. Therefore in December, when construction contracts were let, they included, in addition to laboratory buildings, temporary living quarters for a population of about 300 people. But even before the Ranch School students had left the Hill, construction crews had swelled the population to 1500.

On January 1, 1943 the University of California was selected to operate the new Laboratory and a formal nonprofit contract was soon drawn with the Manhattan Engineer District of the Army. By early spring, major pieces of borrowed equipment were being installed and a group of some of the finest scientific minds in the world were beginning to assemble on the Hill.

The first members of the staff were those who already had been working on related problems at the University of California under J. Robert Oppenheimer. Others came from laboratories all over the country and the world, People like Enrico Fermi, Bruno Rossi, Emilio Segré, Neils Bohr, I. I. Rabi, Hans Bethe, Rolf Landshoff, John von Neumann, Edward Teller, Otto Frisch, Joseph Kennedy, George Kistiakowsky, Richard Feynman and Edwin McMillan came to Los Alamos, some temporarily, some occasionally as consultants and others as permanent members of the staff.

Recruiting was extremely difficult. Most prospective employees were already doing important work and needed good reason to change jobs, but because of the tight security regulations, only scientific personnel could be told anything of the nature of the work to be done. These scientists were able to recognize the significance of the project and be fascinated by the challenge. The administrative people and technicians, on the other hand, were expected to accept jobs in an unknown place for an unknown purpose. Not even wives could be told where the work would take them or why.

“The notion of disappearing into the desert for an indeterminate period and under quasi-military auspices disturbed a good many scientists and the families of many more, ” Oppenheimer recalled later.

The wife of one of the first scientists at the project has written: “I felt akin to the pioneer women accompanying their husbands across uncharted plains westward, alert to dangers, resigned to the fact that they journeyed, for weal or woe, into the Unknown.“

But journey they did, and throughout the spring and summer of 1943 hundreds of bewildered families converged on New Mexico to begin their unforgettable adventure.

The first stop for new arrivals-civilian and military alike-was the Project’s Santa Fe Office at 109 East Palace Avenue. There, under the portal of one of the oldest buildings in Santa Fe, newcomers received a warm welcome from Dorothy McKibbin who was to manage the office for twenty years.

“They arrived, those souls in transit, breathless, sleepless, haggard and tired,” Mrs. McKibbin has written. “Most of the new arrivals were tense with expectancy and curiosity. They had left physics, chemistry or metallurgical laboratories, had sold their homes or rented them, had deceived their friends and launched forth to an unpredictable world."

As their first contact with that unpredictable together to house them. Streets for the town and world, Mrs. McKibbin soothed nerves, calmed fears and softened disappointments. She also supervised shipment of their belongings, issued temporary passes and arranged for their transportation up the hill to Los Alamos.

At the end of the tortuous, winding dirt road, the newcomers found a remarkable city. They found a ramshackle town of temporary buildings scattered helter-skelter over the landscape, an Army post that looked more like a frontier mining camp. “It was difficult to locate any place on that sprawling mesa which had grown so rapidly and so haphazardly, without order or plan,” wrote one early arrival.

Haste and expediency, under the urgency of war, guided every task. Equipment and supplies were trucked from the railhead at Santa Fe while temporary wooden buildings were being hastily thrown roads to remote sites were appearing daily under the blades of countless bulldozers.

The handsome log and stone Ranch School buildings, though nearly obscured by the mushrooming construction, had been converted for Project use. Fuller Lodge had become a restaurant, the classrooms had been converted to a Post Exchange and other shops, the masters’ houses had become residences for top Project administrators. As the only houses in Los Alamos offering tubs instead of showers, this group of buildings quickly became known as “Bathtub Row,” a name that has stuck to this day.

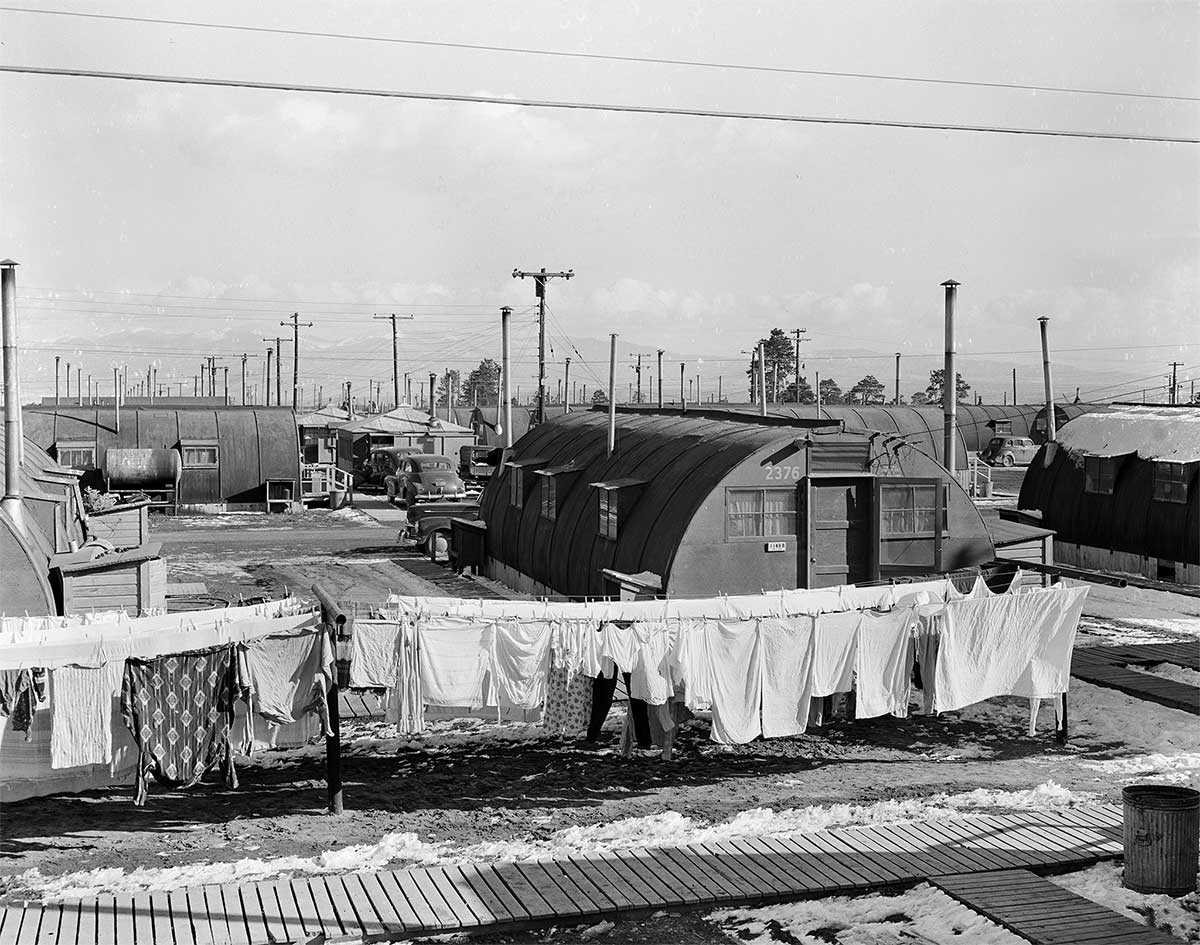

The hurriedly built, green Laboratory buildings sprawled along the south side of Ashley Pond. Rows of four family apartment houses spread to the west along Trinity Drive and northward; rows of barracks and dormitories bordered the apartments and overlooked the horse pastures which are now the Western Area. East of Ashley Pond spread the less luxurious housing including the sections known as McKeeville and Morganville.

The Army did its best to find a place for everyone. Even as the incoming population was spilling over into neighboring valley ranches, to Frijoles Lodge at Bandelier and to Santa Fe, night shift workers, maintenance crews and specialists imported from far away were pouring onto the mesa to be sandwiched in somewhere. The four-family Sundt apartments and the McKee houses were built and occupied at a frantic pace with Pacific hutments, government trailers, expansible trailers and prefabricated units following in jerry-built procession. For more than 20 years the housing never quite managed to catch up with the demand.

This unsightly assortment of accommodations ranged row on row along unpaved and nameless streets. A forest of tall metal chimneys for coal, wood and oil burning stoves and furnaces pierced the air. Soot from furnaces and dust from the streets fell in endless layers on every surface. Winter snows and summer rains left streets and yards mired in mud.

There was only one telephone line (furnished by the Forest Service) when 1943 began and only three until 1945. Dry cleaning had to be sent to Santa Fe until the establishment of a laundry and cleaning concession in the summer of 1944. The first resident dentist arrived in 1944 and a Project hospital was established the same year.

There was never enough water. Dr. Walter Cook, who organized the school system in 1943, remembers the wooden water tank that stood near Fuller Lodge. “It had a gauge on the outside that indicated the water level. It was the only way we could tell when we could take a bath. ”

But life in Los Alamos was not entirely primitive. A 12-grade school system with 16 teachers was established in 1943. A town council was formed the same year, its members elected by popular vote to serve as an advisory committee to the community administration. A nursery school was established for working mothers and a maid service, using Indian women from nearby pueblos, was provided on a rationing system based upon the number and ages of the woman’s children and the number of hours she worked.

More than 30 recreational and cultural organizations were formed during the army years and in 1945 a group, including Enrico Fermi and Hans Bethe, founded a loosely knit Los Alamos University which provided lectures and published lecture notes in fields of nuclear physics and chemistry. Credits from these courses were accepted by leading universities across the country. Home grown talent provided concerts and theatrics and there were movies several times a week.

And there was the country. Los Alamos, for all its ugliness, was surrounded by some of the most spectacular scenery in America.

“Whenever things went wrong, and that was often,” one resident has said, “we always had our mountains—the Jemez on one side, the Sangre de Cristos on the other. ”

But Los Alamos was also surrounded by a high barbed wire fence and armed guards. In what was probably the most secret project the United States has ever had, secrecy became a way of life. Laboratory members were not allowed personal contact with relatives nor permitted to travel more than 100 miles from Los Alamos. A chance encounter with a friend outside the Project had to be reported in detail to the security force.

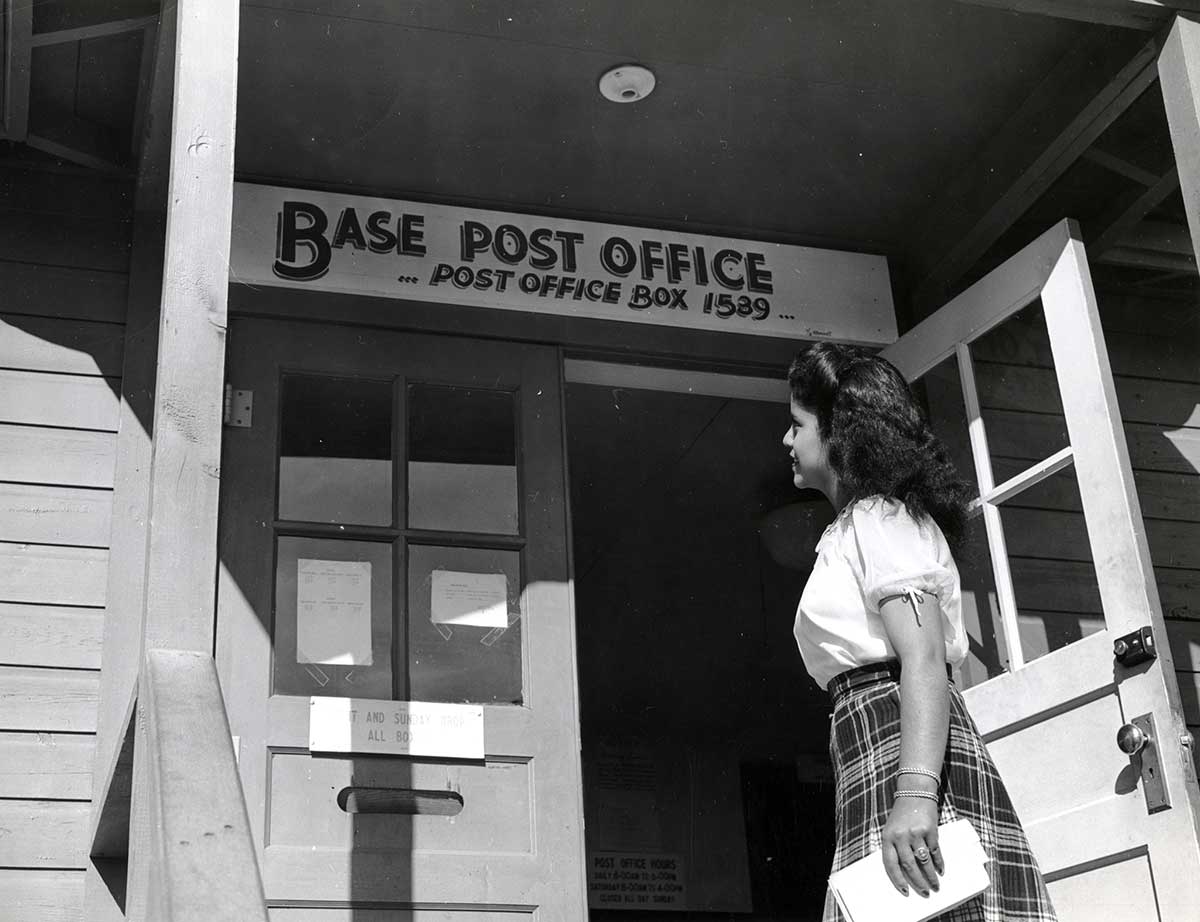

Anonymity prevailed. Famous names were disguised and occupations were not mentioned. Enrico Fermi became “Henry Farmer”, Neils Bohr became “Nicholas Baker.” The word physicist was forbidden; everyone was an “engineer.” Drivers licenses, auto registrations, bank accounts, income tax returns, food and gasoline rations and insurance policies were issued to numbers. Outgoing mail was censored and long distance calls were monitored. No one was permitted to mention names or occupations of fellow residents, to give distances or names of nearby places or even to describe a beautiful view lest the location be pinpointed. Incoming mail was addressed simply to “P.O. Box 1663, Santa Fe, New Mexico,” an obscurity that cloaked the existence of Los Alamos during the entire war.

Recalls one early resident, “I couldn’t write a letter without seeing a censor poring over it. I couldn’t go to Santa Fe without being aware of hidden eyes upon me, watching, waiting to pounce on that inevitable misstep. It wasn’t a pleasant feeling.”

Tight security regulations plagued scientific progress, too. The military insisted that individual not discussed so that no one could see the overall progress-or purpose-of the mission. But Director Oppenheimer, knowing that cross-fertilization of ideas among scientists is infinitely useful in solving problems, balked and as a result weekly colloquia were begun and continue in Los Alamos today. Because of such major victories as this over military rigidity, Oppenheimer is credited not only with the success of the Project but the high morale that made it possible.

The Army years at Los Alamos were a time of chaos and achievement, of unaccustomed hardships and exhausting work. But, as Oppenheimer was to report later, “Almost everyone knew that this job, if it were achieved, would be part of history. This sense of excitement, of devotion and of patriotism in the end prevailed.”