Site Instrumentation

The instrumentation of the test site began in earnest in April 1945, and as scientists completed their assigned work on the bomb at Los Alamos in May and June, many were sent to Trinity to aid in test preparations. The 100-ton test of May 7 had helped determine the final field instrumentation arrangements, and the weeks following were a period of intense activity, with site personnel often working 18 or more hours daily. During this period, the 10,000 south personnel bunker often served as a rendezvous where informal meetings were held, and was used as the control bunker for both the May 7th 100-ton test and the main test on July 16.

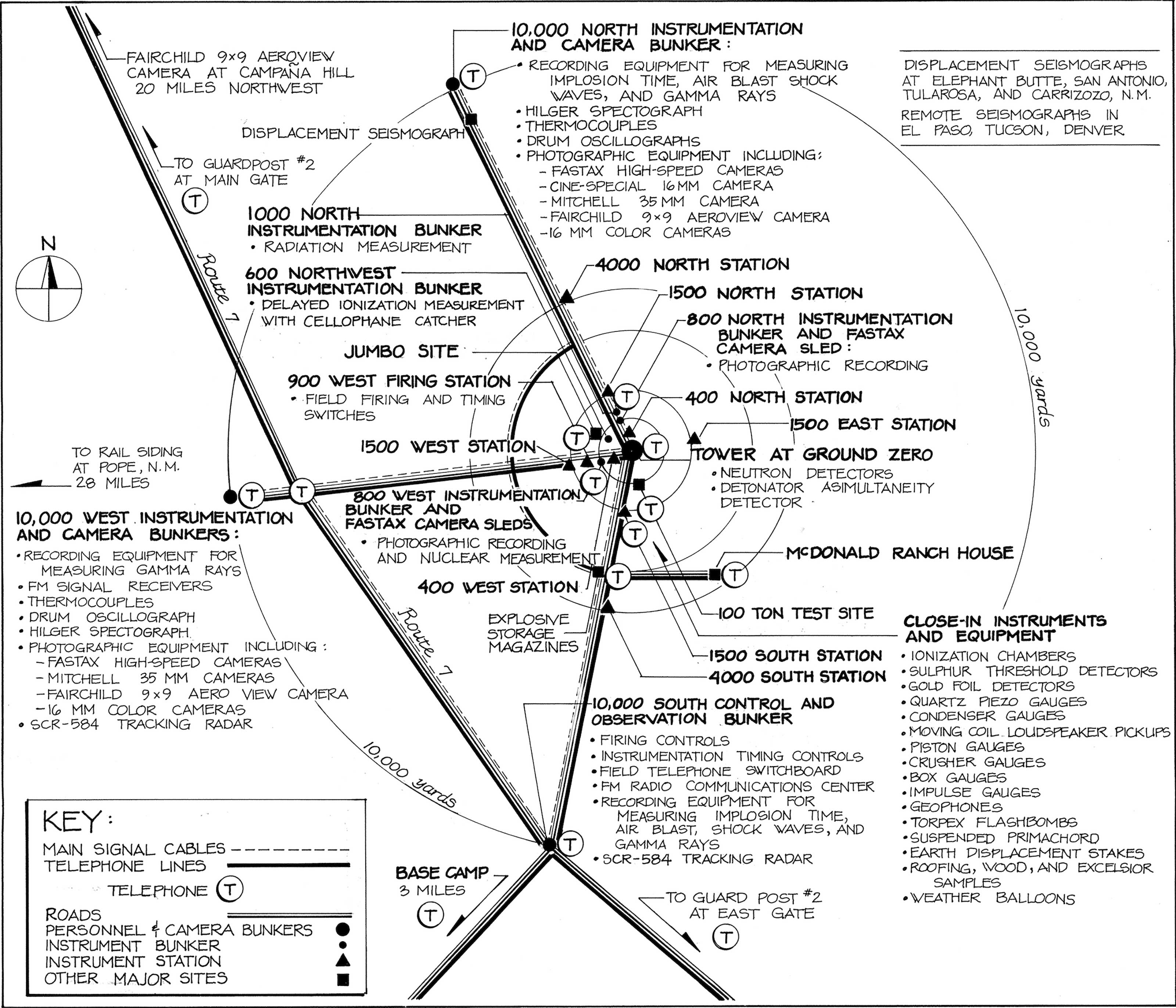

At the direction of the scientists miles of above-ground and buried signal cables were laid between the hundreds of field instruments that covered the desert and their associated timing and recording devices at the 10,000 north, west, and south personnel and camera bunkers. The field instruments were designed to collect information on the specifics of the nuclear implosion process, the bomb's nuclear, air blast, and earth-shock effects, and the behavior of its fireball. Many instruments were exposed above-ground, while others were buried or placed in the instrument bunkers at 1,000 north and 600 northwest. A number of instruments were suspended hours before from the explosion weather balloons. Several weeks prior to the test, the high-speed fastax cameras, which were to be placed at the 800 north and west bunkers, were instead mounted on lead-lined sleds located adjacent to the bunkers. Long cables were attached to the sleds to enable them to be pulled away from the test area within hours of the explosion.

Test instruments and recording devices included oscilloscopes, electron multiplier catcher cameras, chambers, ionization chambers, cellophane sulphur threshold detectors, gold foil detectors, quartz piezo gauges, condenser gauges, moving coil loudspeaker pickups, impulse gauges, piston gauges, crusher, gauges, geophones, seismographs, high-speed cameras, motion picture cameras, gamma ray recorders, spectographs and tracking radar.

The explosion yielded about 15,000 tons of TNT-equivalent and because most of the field instrumentation was set up for a detonation not expected to exceed 5000 tons, many of the test devices were damaged or destroyed by the bomb's intense heat, shock, and radiation effects. Gamma ray emissions blackened the film in many recording instruments within 1,000 yards of ground zero. The electromagnetic impulse given off by the bomb disrupted signals in the shielded cables that ran from site instruments to recorders at the 10,000 yard bunkers, causing a loss of data from many of the close-in experiments. The blast also destroyed the several weather balloons that carried the airborne instruments.

Some data on delayed neutrons were gathered from the cellophane catcher cameras at 600 northwest, and useable readings were obtained from a portion of the field gauges, geophones, seismographs and other test equipment. Most of the cameras at 10.000 north and west worked 10.000 north well during the test, as did the fastax cameras on the lead-lined sleds at 800 north and south. Over 100,000 frames of film were exposed and later analyzed at Los Alamos.

Shortly after the test, a lead-lied tank entered the area near ground zero and retrieved soil samples by the use of rocket fired scoops. These samples, with other ground and airborne matter, were analyzed at Los Alamos to determine the completeness and efficiency of the atomic reaction.