The Bomb

The Los Alamos scientists believed that both uranium- and plutonium -based bombs could be detonated in a gun-type assembly, where one sub-critical mass of fissionable material would be fired into another to achieve the density ("super-critical mass") necessary for a nuclear explosion. By early 1944 however, they found that because of the peculiar characteristics of plutonium, the gun-type method would not work fast enough for this material, and a much more difficult technique, that of "implosion," would have to be employed.

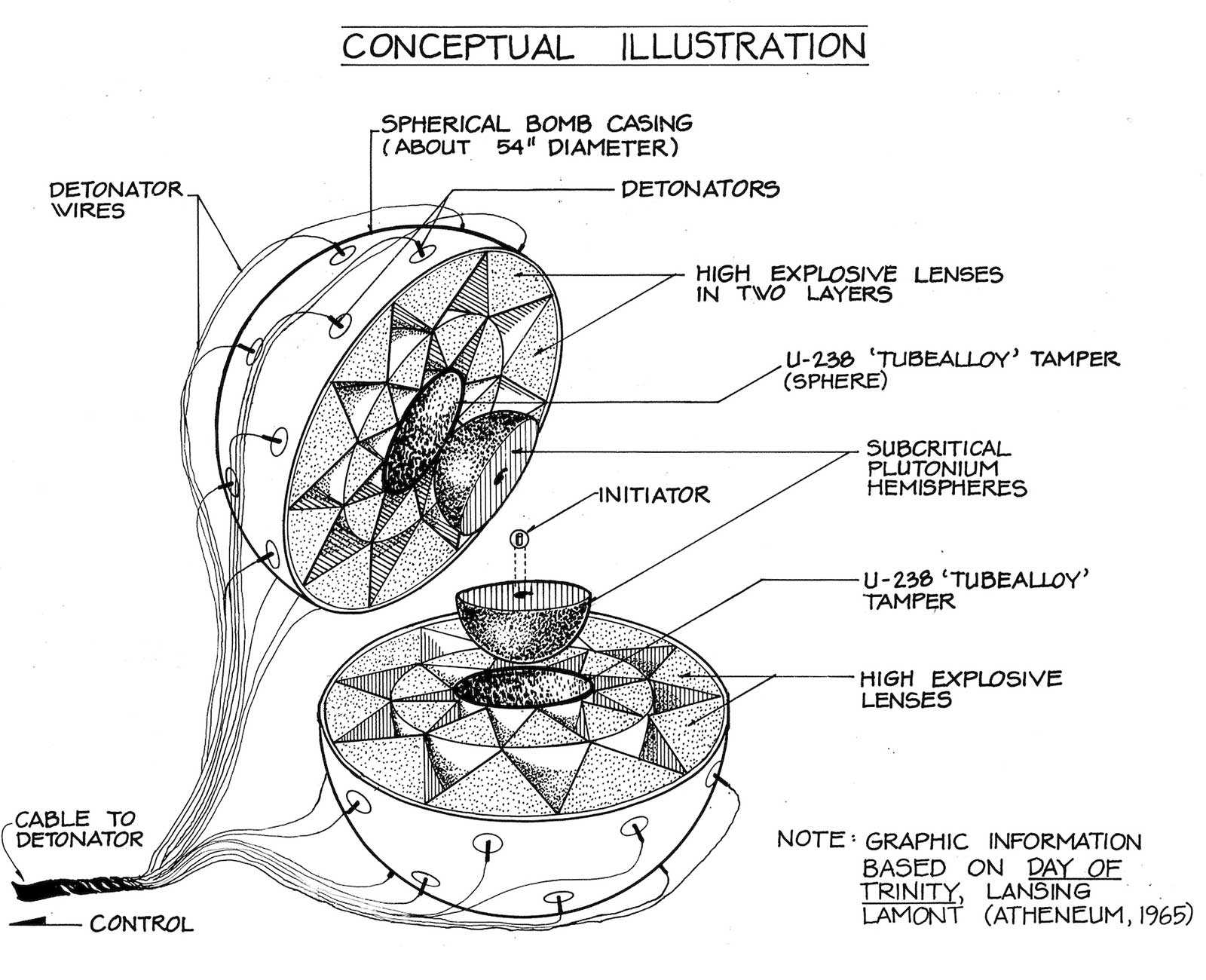

The implosion method involved surrounding a sub-critical sphere of plutonium-239 by high-explosive charges that would, when detonated, uniformly compress the plutonium to a super-critical mass within a few-millionths of a second. The mechanics of creating such an implosion with the necessary degree of speed and symmetry were, however, untried and considered extremely difficult to perfect.

The solution to the implosion problem was a masterpiece of ingenuity and precision. explosive charges were shaped into lenses that upon detonation produced concave shock waves. With the proper design and placement of the lenses, their shock waves would reach the bomb's fissionable core simultaneously and compress it uniformly. extensive work was undertaken at Los Alamos in 1944 to refine the lens configuration, and by April 1945 the problem of symmetrical detonation was solved.

In its final form, the plutonium bomb consisted of three major elements: a fissionable core, two layers or high-explosive lenses, and a set of detonators. containing tivo hemispheres of plutonium with the core, an "initiator" between them, was surrounded by a uranium "tamper." Upon detonation of the high-explosive lenses and the subsequent compression of the core, the initiator released a burst of neutrons that began the chain reaction. the tamper acted as a reflective shield to contain the neutrons until the chain reaction was well underway