Los Alamos: Beginning of an Era 1943-1945

Countdown

The air hung heavy over the Hill that summer. Rains failed to come and precipitation was half the normal amount. Temperatures rose to average four degrees above normal. Water became scarce and fires threatened, adding to the irritations and frustrations.

Dorothy McKibbin, who ran the Santa Fe liaison office for the Los Alamos project, could discern the tightening of tensions on the Hill, but because of rigid security, she had only her intuition to tell her what was happening. As many as 70 people checked into her office every day and one day she counted 100 phone calls. “The voices on the telephone showed strain and tautness, and I sensed we were about to reach some kind of climax in the project,” she recalls.

In the Laboratory, one or two hour meetings, attended by consultants, group and section leaders involved in the Trinity Project, were being held every Monday for consideration of new experiments, correlation of the work, detailed scheduling and progress reports.

One of the most important corrective measures resulting from the 100-ton test had been the setting of a date after which further apparatus, particularly electrical equipment, could not be introduced into the experimental area. The deadline would allow plenty of time for dry runs and would reduce the risk of last minute damage to electrical connections. In view of this, proposed experiments were described in writing in great detail and submitted to a special examining committee. If approved they were then submitted to the Monday meetings where they were considered with respect to the test programming as a whole before being accepted. “Any new experiment had to be awfully good to be included after the deadline.” Bainbridge reports.

For about a month before the test, John Williams held nightly meetings at Trinity to hear reports on field construction progress and to plan the assignment of men for the following day. Construction help was assigned on the basis of needs and priority of experiments which had been accepted for the test.

Meanwhile, J. M. Hubbard, who had joined the Trinity Project early in April, as meteorology supervisor, had undertaken the job of determining the best test date from a weather point of view.

Weather was a vital factor. Clear weather was best suited to observation planes in the air and visual and photographic measurements on the ground. Rain before or during the test could damage electrical circuits both for firing the gadget and operating the instruments. Only six months before the test, according to General Groves Joseph Hirschfelder, a Los Alamos physicist, had first brought up the possibility that fallout might be a real problem. For this reason it was considered essential that wind direction be such that the radioactive cloud would not pass over inhabited areas that might have to be evacuated, and there should be no rain immediately after the shot which would bring concentrated amounts of fallout down on a small area.

Using reports from each group on the particular weather conditions or surveys they would find most useful and coordinating them with complete worldwide weather information, Hubbard ultimately pinpointed July 18-19 or 20-21 as the ideal date with July 12-14 as second choice. July 16 was mentioned only as a possibility.

However, on June 30 a review of all schedules was made at a Cowpuncher meeting for which all division leaders had submitted the earliest possible date their work could be ready. On the basis of these estimates, July 16 was established as the final date. From the beginning, estimates of the success of the gadget had been conservative. Although safety provisions were made for yields up to 20,000 tons, test plans were based on yields of 100 to 10,000 tons, By as late as July 10 the most probable yield was set at only 4,000 tons.

Scientists not directly involved in the test established a pool on the yield and the trend was definitely toward the lower numbers, except for Edward Teller’s choice of around 45,000 tons. Oppenheimer himself reputedly picked 200 tons and then bet $10 against Kistiakowsky’s salary that the gadget wouldn’t work at all. (I. I. Rabi, project consultant, won the pool with a guess of 18,000 tons, a number he picked only because all the low numbers had been taken by the time he entered the contest.) It was not just the yield that was in doubt. Even as the scientists went about the last few weeks of preparations, the nagging uncertainty persisted about whether the bomb would work at all. This air of doubt is depicted in a gloomy parody said to have circulated around the Laboratory in 1945:

“From this crude lab that spawned a dud

Their necks to Truman’s axe uncurled

Lo, the embattled savants stood

And fired the flop heard round the world.”

Then, as if things weren’t looking dismal enough, a meeting of Trinity people held just before the test heard Hans Bethe describe in depressing detail all that was known about the bomb, and all that wasn’t. Physicist Frederick Reines remembers the utter dejection he felt after hearing the report. “It seemed as though we didn’t know anything, ” he said.

It was only natural, Bethe wrote later, that the scientists would feel some doubts about whether the bomb would really work. They were plagued by so many questions: Had everything been done right? Was even the principle right? Was there any slip in a minor point which had been overlooked? They would never be sure until July 16.

By the first week in July, plans were essentially complete and the hectic two weeks that remained were devoted to receiving and installing equipment, completing construction, conducting the necessary tests and dry runs and, finally, assembling the device.

The plans, as described in the official AEC history, “The New World,” were these:

“Working in shelters at three stations 10,000 yards south, west and north of the firing point, teams of scientists would undertake to observe and measure the sequence of events. The first task was to determine the character of the implosion. Kenneth Greisen and Ernest Titterton would determine the interval between the firing of the first and last detonators. This would reveal the degree of simultaneity achieved. Darol Froman and Robert R. Wilson would calculate the time interval between the action of the detonators and the reception of the first gamma rays coming from the nuclear reaction. From this value they hoped to draw conclusions as to the behavior of the implosion. With Bruno Rossi’s assistance, Wilson would also gauge the rate at which fissions occurred.

“Implosion studies were only a start. The second objective was to determine how well the bomb accomplished its main objective—the release of nuclear energy. Emilio Segre would check the intensity of the gamma rays emitted by the fission products, while Hugh T. Richards would investigate the delayed neutrons. Herbert L. Anderson would undertake a radiochemical analysis of soil in the neighborhood of the explosion to determine the ratio of fission products to unconverted plutonium. No one of these methods was certain to provide accurate results, but the interpretation of the combined data might be very important.

“The third great job at Trinity was damage measurements. John H. Manley would supervise a series of ingenious arrangements to record blast pressure. Others would register earth shock while William G. Penney would observe the effect of radiant heating in igniting structural materials. In addition to these specific research targets, it was important to study the more general phenomena.

This was the responsibility of Julian E. Mack. His group would use photograph; and spectrographic observations to record the behavior of the ball of fire and its aftereffects.” Some cameras would take color motion pictures, some would take black and white at ordinary speeds and others would be used at exceedingly high speeds, up to 8000 frames per second, in order to catch the very beginning of the blast wave in the air. There also would be several spectrographs to observe the color and spectrum of the light emitted by the ball of fire in the center of the blast.

Observation planes, one of them carrying Capt. Parsons, head of the overseas delivery project, would fly out of Albuquerque making passes over the test site to simulate the dropping of a bomb. They would also drop parachute-suspended pressure gauges near Ground Zero. One of the main reasons for the planes would be to enable Parsons to report later on the relative visual intensity of the explosion of the test bomb and that of the bomb to be dropped on Japan.Plans also were made to cover the legal and safety aspects of the test.

To protect men and instruments, the observation shelters would be located 10,000 yards from Ground Zero and built of wood with walls reinforced with concrete and buried under huge layers of earth. Each shelter was to be under the supervision of a scientist until the shot was fired at which time a medical doctor would assume leadership. The medics were familiar with radiation and radiation instruments and would be responsible for efficient evacuation of the shelters on designated escape routes in case of emergency. Vehicles would be standing by ready to leave on a moments notice, manned by drivers familiar with the desert roads at night. Commanding the shelters would be R. R, Wilson and Dr. Henry Barnett at N 10,000, John Manley and Dr. Jim Nolan at W 10,000 and Frank Oppenheimer and Dr. Louis Hemplemann at S 10,000,

A contingent of 160 enlisted men under the command of Major T. O. Palmer were to be stationed north of the test area with enough vehicles to evacuate ranches and towns if it became necessary and at least 20 men with Military Intelligence were located in neighboring towns and cities up to 100 miles away serving a dual purpose by carrying recording barographs in order to get permanent records of the blast and earth shock at remote points for legal purposes.

On July 5, just six days after enough plutonium had been received, Oppenheimer wired Project consultants Arthur H. Compton in Chicago and E. O. Lawrence in Berkeley: “Anytime after the 15th would be a good time for our fishing trip. Because we are not certain of the weather we may be delayed several days. As we do not have enough sleeping bags to go around, we ask you please not to bring any one with you,” There wasn’t much sleeping being done anywhere at Trinity those last frantic days. There were about 250 men from Los Alamos at the test site doing last minute technical work and many more were in Los Alamos contributing to the theoretical and experimental studies and in the construction of equipment. And all of them were working against time.

“The Los Alamos staff was a dedicated group,” John Williams is quoted as saying some years later “It was not uncommon to have a 24 hour work day at the end. ”

On July 1 the final schedule was broadcast at Trinity and circulated around the camp two days later. Rehearsals would be held July 11, 12, 13 and 14. Originally scheduled to be held in the afternoon, the times were changed after the first dry run when daily afternoon thunderstorms began to interfere with the flight of the observation planes and to produce electrical interference and pick up on the lines.

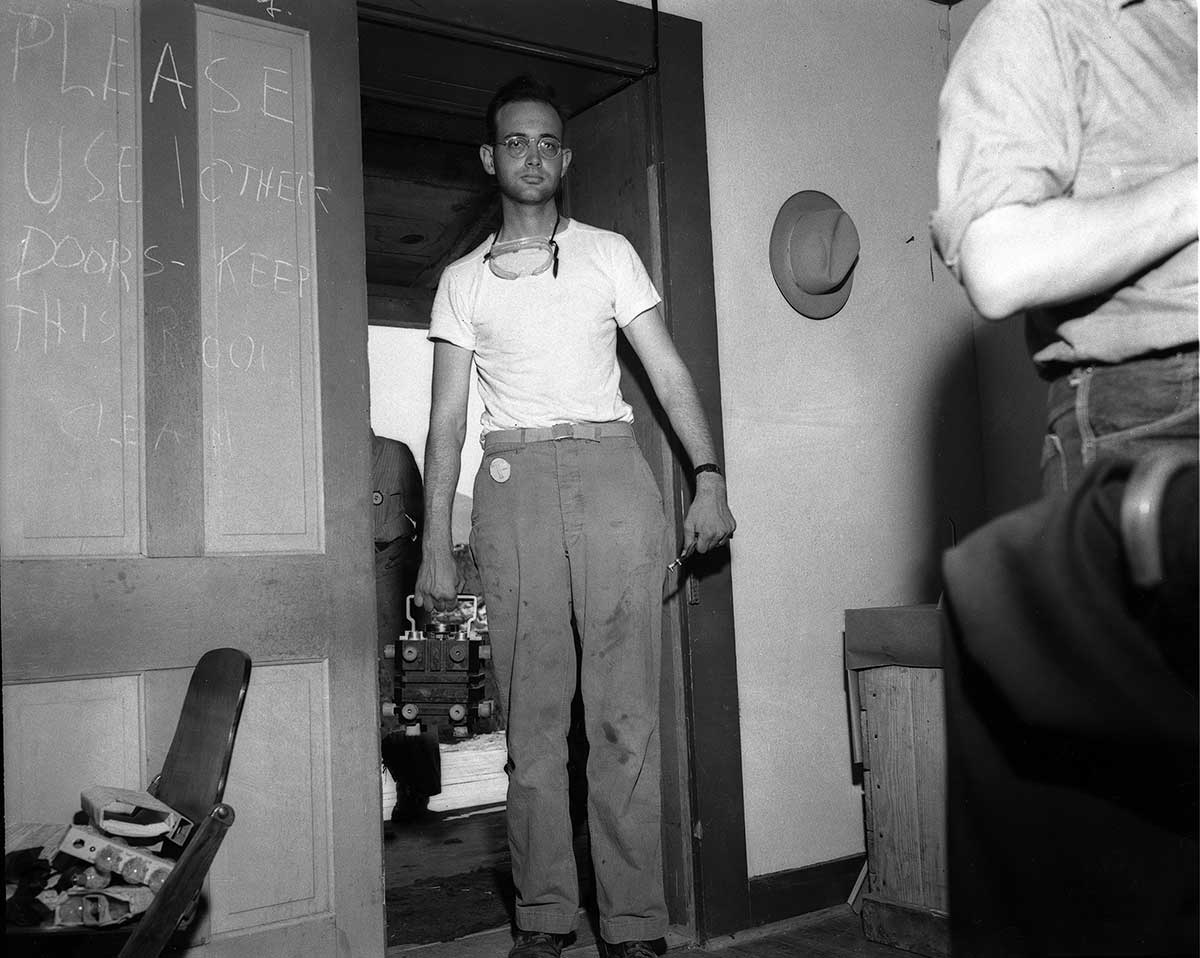

Meanwhile, Norris Bradbury, group leader for bomb assembly, had issued his countdown. Beginning on July 7 in Los Alamos the high explosive components were put through a number of tests to study methods of loading and the effects of transportation and a dry run on the assembly. On July 10 the crew began the tedious round-the-clock preparations of the components for delivery to Trinity, using night shifts to get the job done. Thursday, July 12, assembly began at V site and by late that night they were ready to “seal up all holes in the case; wrap with scotch tape (time not available for strippable plastic), and start loading on truck. ”

At 1 a.m. on Friday, July 13, the pre-assembled high explosive components started for Trinity in a truck convoyed by Army Intelligence cars in front and behind with George Kistiakowsky accompanying the precious cargo in the forward car.

The two hemispheres of plutonium made the trip to Trinity from Los Alamos on July 11, accompanied by a Lt. Richardson and several soldiers in a convoyed sedan and delivered to Bainbridge at the tower. A receipt for the plutonium was requested.

“I was very busy and we were fighting against time, ” Bainbridge recalled recently. “I thought "What kind of foolishness is this," and directed the men to the assembly site at McDonald ranch.”

Bainbridge remembers that Richardson and his crew seemed awfully eager to get rid of their strange cargo even though they weren’t supposed to know the real significance of it.

Eventually the receipt was signed at the ranch by Brig. Gen. T. F. Farrell, Groves’ deputy, and handed to Louis Slotin who was working on nuclear assembly. The acceptance of the receipt signaled the formal transfer of the precious Pu-239 from the Los Alamos scientists to the Army for use in a test explosion. Nuclear tests and the assembly of the active components were completed at the ranch and shortly after noon on Friday the 13th final assembly of the bomb began in a canvas tent at the base of the tower.

Bradbury’s detailed step-by-step instructions for the assembly process, which was interrupted at frequent intervals for “inspection by generally interested personnel, ” show the careful, gingerly fashion in which the crew approached its history-making job.

“Pick up GENTLY with hook.”

“Plug hole is covered with a CLEAN cloth.”

“Place hypodermic needle IN RIGHT PLACE.

Check this carefully.”

“Insert HE–to be done as slowly as the G (Gadget) engineers wish. . . . Be sure shoe horn is on hand.”

“Sphere will be left overnight, cap up, in a small dish pan.”

By late afternoon the active material and the high explosive came together for the first time.

Neither Bradbury nor Raemer Schreiber, a member of the pit assembly crew, remembers any particular feeling of tension or apprehension during the operation although, Bradbury said, “There is always a certain amount of concern when you are working with high explosives.”

“We were given plenty of time for the assembly of active material,” Schreiber remembers. “By then it was pretty much a routine operation. It was simply a matter of working very slowly and carefully, checking and re-checking everything as we went along.”

The assembly departed from the routine only once, when the crew made the startling discovery that the two principal parts of the gadget, carefully designed and precision machined, no longer fit together. Marshall Holloway, in charge of pit assembly, came to the rescue and in only a couple of minutes had the problem solved.

The plutonium component, which had generated a considerable amount of its own heat during the trip from Los Alamos, had expanded. The other section of the assembly had remained cold. The heat exchange resulting when the hot material was left in contact with the cold for only a minute or two soon had the two pieces slipping perfectly together.

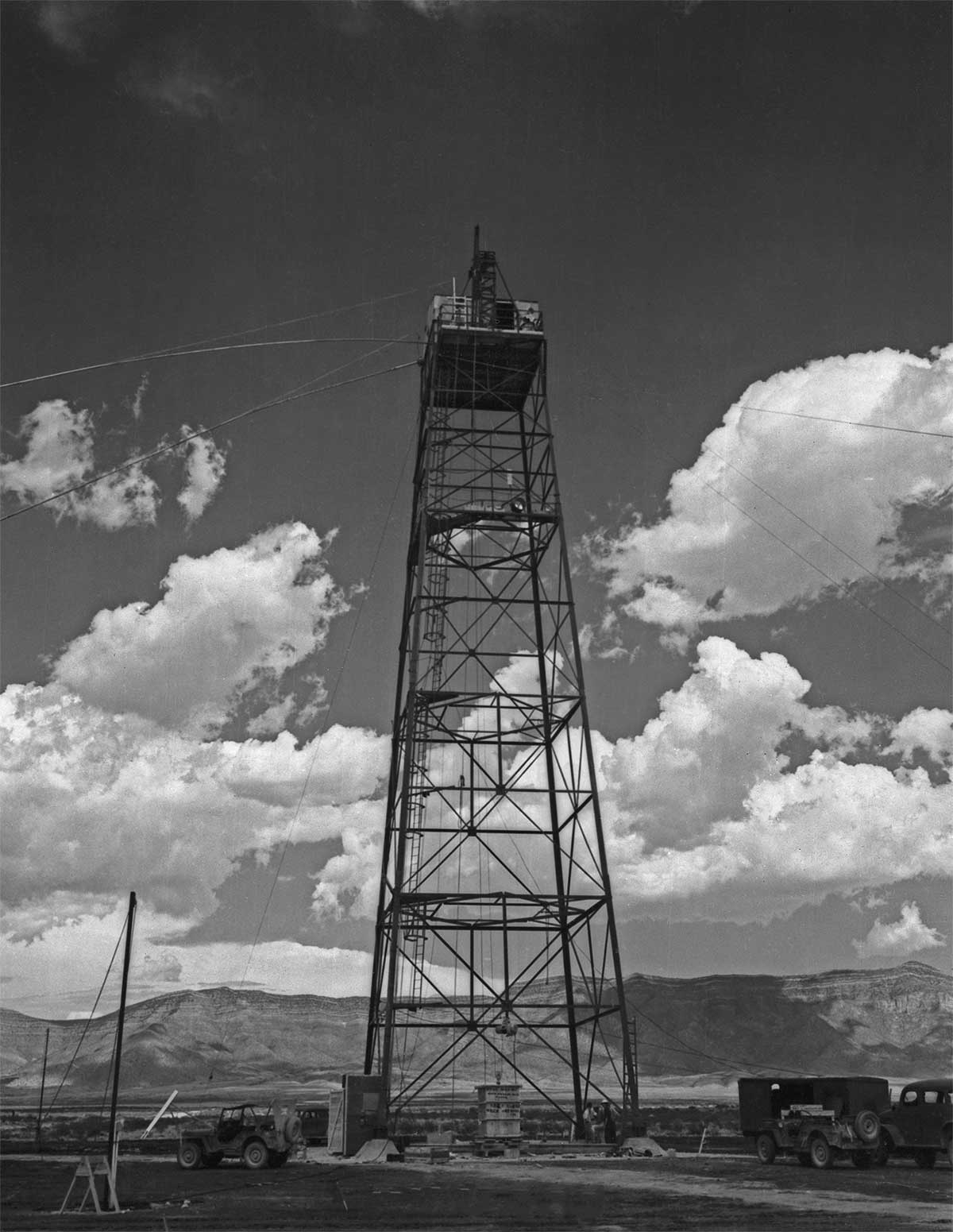

Early the next morning the tent was removed and the assembled gadget was raised to the top of the 100-foot tower where it rested in a specially constructed sheet steel house. But it was still without detonators.

“Detonators were very fragile things in those days,” Bradbury explained. “We didn’t want to haul that gadget around with the detonators already in it. We might have dropped it. ”

So it was up to the detonator crew, headed by Kenneth Greisen, to climb the tower and make the final installations and inspections and to return every six hours to withdraw the manganese wire . whose induced radioactivity was a measure of neutron background. The necessary cables were connected to a dummy unit which would permit tests to continue while the bomb was armed.

Late that night the job was essentially complete. The gadget was left in the care of an armed guard and the scientists and technicians were left with only the final routine preparations and last-minute adjustments on their equipment.

All planes at the Alamogordo base were grounded until further notice and arrangements had been made with the Civil Aeronautics Authority, the apprehension Corps and Navy to insure that the entire area would be barred to all aircraft during the last important hours.

According to General Groves, it was quite upsetting to the base, for it was there that B-29 crews received their final training. before leaving for the Pacific and every unit commander wanted his crew to have as many hours in the air as possible. All they knew was that their training schedules were being upset for some unexplained reason. Many men, Groves continued, were already on the landing field when the explosion occurred and not long after several thousand men were preparing for take-offs.

Meanwhile, the high-ranking observers began to assemble. On Sunday afternoon General Groves, who had been touring Manhattan District installations on the West Coast in order to be nearby in case the test hour was advanced, arrived at Trinity with Vannevar Bush and James B. Conant, members of the MED’s policy committee. A busload of consultants from Project Y left Los Alamos for the desert and automobiles were dispatched to Santa Fe to pick up Charles A. Thomas, MED’s coordinator for chemical research, and to Albuquerque for Ernest O. Lawrence, Sir James Chadwick and William L. Laurence of the New York Times, the one newsman assigned by the Manhattan District to document the development of the bomb.

At the test site, after months of hectic activity, things became more relaxed as the final items on Bradbury’s hot run countdown indicate:

“Sunday, 15 July, all day: look for rabbit’s feet and four-leafed clovers. Should we have the chaplain down there? Period for inspection available from 0900-1000.

Monday, 16 July, 0400: BANG!”

But it wasn’t quite as simple as that. By Sunday evening the skies had darkened, thunder rolled in the surrounding mountains and lightning cracked through the overcast. It began to rain. Now that the test was ready, at long last, could it actually go?

Shortly before 11 p.m. Sunday night the arming party, consisting of Bainbridge, Kistiakowsky, Joe McKibben, two Pinny weathermen, Lt. Bush and a guard, assembled at the base camp for the final trip to the tower.

McKibben, who had the very important and punishing job of supplying the timing and remote operating signals, was dead tired. “He had had a more trying time for two weeks than most of us, ” Bainbridge recalled. “Any one of 50 people with special test equipment who, needed timing and activating signals over their control wires had been asking McKibben and his group for rehearsals at all hours of the day and night for two weeks with very large amounts of business the week prior to July 16.”

But tired or not, McKibben had with him a two page check list of 47 jobs to be done before Zero hour. His preliminary jobs were finished by 11 and he was urged to get some sleep. “I remember he looked absolutely white with fatigue,” Bainbridge said, “and we wanted him alert and ready at test time. ”

Donald Hornig came out, went to the top of the tower to switch the detonating circuit from the dummy practice circuit to the real gadget and then returned to S 10,000 where he would be responsible for the “stop” switch. If anything went wrong while the automatic devices were operating seconds before the detonation, he would pull the switch and prevent the explosion.

Kistiakowsky climbed about 30 feet up the tower to adjust a light at the radioed request of a cameraman and then returned to the car to sleep. Periodically Lt. Bush or the guard turned their flashlights on the tower to make certain there was no one trying to interfere with the cables. Hubbard and his assistants continued with their weather measurements while Bainbridge kept in touch with John Williams on the land telephone at S 10,000.

“It was raining so hard,” McKibben remembers, “I dreamed Kisti was turning a hose on me.” There was lightning, too, but not dangerously close to the tower. The rain continued. Back at the control dugout Oppenheimer and General Groves consulted through the night.

“Every five or ten minutes Oppenheimer and I would go outside and discuss the weather,” Groves writes. “I was shielding him from the excitement swirling about us so that he could consider the situation as calmly as possible. ” Fortunately, Groves continues, “although there was an air of excitement at the dugout, there was a minimum of conflicting advice and opinions because everyone there had something to do, checking and re-checking the equipment under their control. ”

At 1 a.m. Groves urged the director to get some sleep. Groves himself joined Bush and Conant in a nearby tent for a quick nap without much luck. “The tent was badly set up,” Groves recalls, “and the canvas slapped constantly in the high wind. ”

By 2 a.m. the weather began to look better and it was decided that the shot probably could be fired that morning, but instead of the planned hour of 4 a.m. it was postponed until 5:30. The waiting and checking continued.

The rain stopped at 4:00 a.m. At 4:45 a.m. the crucial weather report came: “Winds aloft very light, variable to 40,000 surface calm. Inversion about 17,000 ft. Humidity 12,000 to 18,000 above 807.. Conditions holding for next two hours. Sky now broken becoming scattered. ” The wind directions and velocities at all levels to 30,000 feet looked good from a safety standpoint. Bainbridge and Hubbard consulted with Oppenheimer and General Farrell through Williams on the telephone. One dissenting vote could have called off the test. The decision was made. The shot would go at 5: 30.

The arming party went into action. Bainbridge, McKibben and Kistiakowsky drove with Lt. Bush to the west 900 yard point where, according to McKibben’s check list, he “opened all customer circuits.” Back at the tower connections were checked, switches were thrown and arming, power, firing and informer leads were connected. Bainbridge kept in touch with Williams by phone, reporting each step before it was taken.

“In case anything went sour,” Bainbridge explained, “the S 10,000 group would know what had messed it up and the same mistake could be avoided in the future. ”

The lights were switched on at the tower to direct the B-29s and the arming party headed for the control point at S 10,000, driving, they all insist, at the reasonable rate of about 25 miles an hour.

Arriving at S 10,000 about 5 a.m. Bainbridge broadcast the weather conditions so that leaders at the observation points would have the latest information and know what to worry about in the way of fallout

Then from Kirtland Air Force Base came word from Captain Parsons. Weather was bad at Albuquerque and the base commander did not want the planes to take off. But the decision was already made.

Later the planes did take off but because of overcast only fleeting glimpses of the ground could be seen and Parsons was barely able to keep the plane oriented. Unable to drop their gauges with any degree of accuracy the airborne group became merely observers.

Just after 5 Bainbridge used his special key to unlock the lock that protected the switches from tampering while the arming party was at the tower. At 5:10 a.m. Sam Allison began the countdown. All through the night the spectators had been gathering to await the most spectacular dawn the world had ever seen.

They waited on high ground outside the control bunker. They waited at the observation posts at West and North 10,000. They waited in arroyos and in surrounding hills. A group of guards waited in slit trenches in Mockingbird Gap between Oscuro and Little Burro Peaks.

All had been instructed to lie face down on the ground with their feet toward the blast, to close their eyes and cover them as the countdown approached zero. As soon as they became aware of the flash they could turn over and watch through the darkened glass that had been supplied.

On Compagna Hill, 20 miles northwest of Ground Zero, a large contingent of scientists waited along with Laurence of the Times. They shivered in the cold and listened to instructions read by flashlight by David Dow, in charge of that observation post. They ate a picnic breakfast. Edward Teller warned about sunburn and somebody passed around some sunburn lotion in the pitch darkness.

Fred Reines, a former Los Alamos physicist, waited with Greisen and I. I. Rabi, a project consultant, and heard the “Voice of America” burst forth on the short wave radio with “Star Spangled Banner” as if anticipating a momentous event.

Al and Elizabeth Graves, a husband and wife scientific team, waited in a dingy Carrizozo motel with their recording instruments. Others, mostly military men, waited at spots as far away as 200 miles, their instruments ready to record the phenomena.

In San Antonio, Restaurant Proprietor Jose Micra was awakened by the soldiers stationed at his place with seismographs. “If’ you come out in front of your store now, you’ll see something the world has never seen before, ” they told him.

Just south of San Antonio, a group of hardy Los Alamos souls, who had climbed into the saddle of Chupadero Peak the day before, waited drowsily in their sleeping bags.

In Los Alamos, most people slept but some knew and went out to watch from the porches of their Sundt apartments. Others drove into the mountains for a better view. Mr. and Mrs. Darol Froman and a group of friends waited in their car, gave up and were heading back down the mountain when 5:30 came.

A group of wives, whose husbands had been off in the desert for endless weeks, waited in the chill air of Sawyer’s Hill. Months later one of them described the agonizing hours.

“Four o’clock. Nothing was happening. Perhaps something was amiss down there in the desert where one’s husband stood with other men to midwife the birth of the monster. Four fifteen and nothing yet. Maybe it had failed. At least, then, the husbands were safe. . . . Four thirty. The gray dawn rising in the east, and still no sign that the labor and struggle of the past three years had meant anything at all. . . . It hardly seemed worthwhile to stand there, scanning the sky, cold and so afraid.” Elsewhere the world slept or fought its war and President Truman waited at Potsdam.

Back at Trinity, over the intercoms, the FM radios, the public address system, Sam Allison’s voice went on, counting first at five-minute intervals then in interminable seconds.

“Aren’t you nervous?” Rabi asked Greisen as they lay face down on the ground.

“Nope,” replied Greisen.

“As we approached the final minute,” Groves wrote, “the quiet grew more intense. I was on the ground (at Base Camp) between Bush and Conant. As I lay there in the final seconds, I thought only of what I would do if the countdown got to zero and nothing happened.” Conant said he never knew seconds could be so long.At the control point, General Farrell wrote later, “The scene inside the shelter was dramatic beyond words. . . . It can be safely said that most everyone present was praying. Oppenheimer grew tenser as the seconds ticked off. He scarcely breathed. He held on to a post to steady himself.”

The countdown went on. At minus 45 seconds Joe McKibben threw the switch that started the precise automatic timer. Now it was out of man’s control, except for Hornig who watched at his post at the stop switch.

Minus 30 seconds, and Williams and Bainbridge joined the others outside the control dugout. Minus 10 seconds. Cool-headed Greisen changed his mind, “Now I’m scared,” he suddenly blurted to Rabi.

Then, as the world teetered on the brink of a new age, Sam Allison’s voice cried, “Now!”