Los Alamos: Beginning of an Era 1943-1945

The Plans

The first formal arrangements for the test were made in March 1944 with the formation, in George Kistiakowsky’s Explosives Division, of group X-2 under the leadership of Kenneth T. Bainbridge, whose duties were “to make preparations for a field test in which blast, earth shock, neutron and gamma radiation would be studied and complete photographic records made of the explosion and any atmospheric phenomena connected with the explosion.”

With doubt and uncertainty hanging over the project throughout 1944 it is not surprising that one of the first and most heavily emphasized efforts in the test preparations was planning for the recovery of active material in case the nuclear explosion failed to take place. In 1944 there was barely enough plutonium available to conduct the essential experiments and the outlook for increased production was dim. It seemed absolutely essential that the active material not be wasted in an unsuccessful test.

Scientists toyed with the idea of using a water recovery method in which the bomb, surrounded by air space, would be suspended in a tank of water and fragments would be stopped by a 50 to 1 ratio of water to high explosive mass. They also investigated the possibility of detonating the bomb over a huge sand pile and putting the sand through placer operations to mine whatever plutonium might be embedded there. Neither of these methods appeared particularly promising and the decision was made early in the Same to attempt to contain the blast in a huge steel vessel.

Although the container, promptly dubbed Jumbo, became a high priority project at the outset and all test plans, until the last minute, were based on the assumption that it would be used, there is little evidence that the idea met with much enthusiasm in Los Alamos.

As early as March 10, 1944, Oppenheimer wrote to General Groves outlining the plans and possibilities for “a sphere for proof firing”, pointing out that “the probability that the reaction would not shatter the container is extremely small.” He promised, however, that the Laboratory would go ahead with plans and fabrication of the vessel. But this was easier said than done, and by the following summer Jumbo had become the most agonizing of the project’s endless procurement headaches.

In late March, Hans Bethe, head of the Theoretical Division, wrote in a memo to Oppenheimer that because of the numerous engineering problems, which he described in discouraging detail, “the problem of a confining sphere is at present darker than ever. ”

But the problem was tackled, nonetheless, by section X2-A of Bainbridge’s group with R. W. Henderson and R. W. Carlson responsible for engineering, design and procurement of the vessel. In May scale model “Jumbinos” were delivered to Los Alamos where numerous tests were conducted to prove the feasibility of the design.

Feasible though the design appeared to be, there was scarcely a steel man in the country who felt he could manufacture the container. Specifications required that Jumbo must, without rupture, contain the explosion of the implosion bomb’s full complement of high explosive and permit mechanical and chemical recovery of the active material. To do this required an elongated elastic vessel 25 feet long and 12 feet in diameter with 14 inch thick walls and weighing 214 tons.

Personal letters explaining the urgency of the project and the importance of the specifications went out from Oppenheimer to steel company heads, but by May 23, 1944, Oppenheimer was forced to report to his Jumbo committee that the steel companies approached had expressed strong doubts that Jumbo could be manufactured to specifications. Meanwhile, he told them, feasibility experiments would continue in the Jumbinos and the order for the final vessel would be delayed a little longer. Eventually, the Babcock and Wilcox Corporation of Barbel-ton, Ohio agreed to take a crack at the job and the order was placed in August, 1944. The following spring the tremendous steel bottle began its roundabout trip from Ohio on a specially built flat car, switching from one route to another wherever adequate clearance was assured. In May 1945, the jug was delivered to a siding, built for the purpose by the Manhattan District, at Pope, New Mexico, an old Santa Fe railroad station that served as a link with the Southern Pacific and the Pacific Coast in the 1890’s. There it was transferred to a specially built 64-wheel trailer for the overland trip to the test site.

But it was too late. During the last months before the test, all of the elaborate recovery schemes were abandoned. By then there was greater promised production of active material, there was greater confidence in the success of the bomb and, more importantly, there was increasing protest that Jumbo would spoil nearly all the sought-after measurements which were, after all, the prime reason for conducting the test at all.

The fate of Jumbo, however, was not absolutely settled until the very last minute. On June 11, 1945, just a month before the test, Bainbridge, in a memo to Norris Bradbury, present Laboratory director and then in charge of bomb assembly, wrote that “Jumbo is a silent partner in all our plans and is not yet dead. . . We must continue preparations for (its) use until Oppenheimer says to forget it for the first shot. ”

And a silent partner it remained, Ultimately the magnificent piece of engineering was erected on a tower 800 feet from Ground Zero to stand idly by through the historic test.

Once the decision had been made, in the spring of 1944, to conduct the test, the search began for a suitable test site. Los Alamos was ruled out immediately for both space and security reasons and the search spread to eight possible areas in the western United States,

To please the scientists, security and safety people alike, the site requirements were numerous. It had to be flat to minimize extraneous effects of the blast. Weather had to be good on the average with small and infrequent amounts of haze and dust and relatively light winds for the benefit of the large amounts of optical information desired. For safety and security reasons, ranches and settlements had to be few and far away. The site had to be fairly near Los Alamos to minimize the loss of time in travel by personnel and transportation of equipment, yet far enough removed to eliminate any apparent connection between the test site and Los Alamos activities. Convenience in constructing camp facilities had to be considered. And there was the everpresent question: Could Jumbo be readily delivered there?

Throughout the spring a committee, composed of Oppenheimer, Bainbridge, Major Peer de Silva, Project intelligence officer, and Major W. A. Stevens, in charge of maintenance and construction for the implosion project, set out by plane or automobiles to investigate the site possibilities. They considered the Tularosa Basin; a desert area near Rice, California; San Nicholas Island off Southern California; the lava region south of Grants; an area southwest of Cuba, New Mexico; sand bars off the coast of South Texas; and the San Luis Valley region near the Great Sand Dunes National Monument in Colorado.

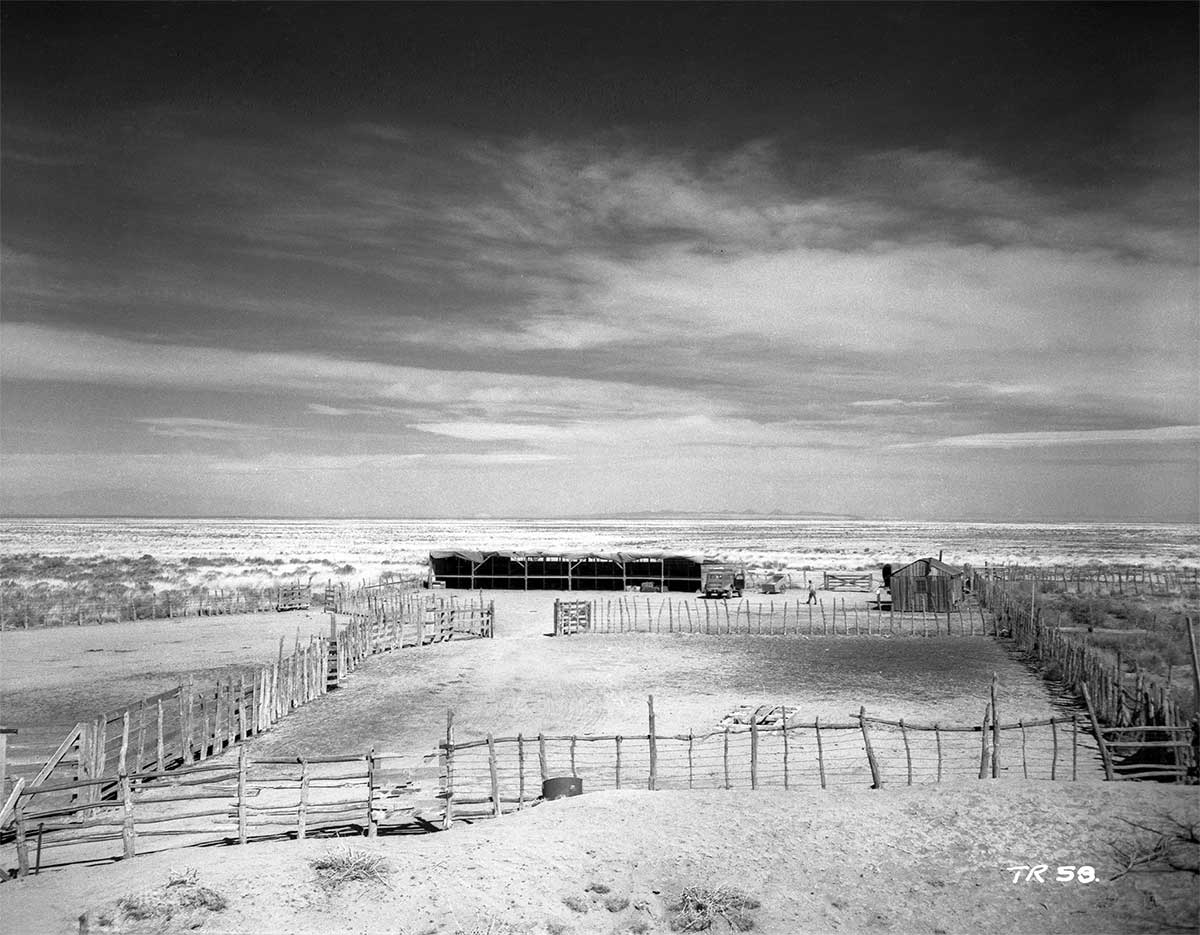

By late summer the choice was pretty well narrowed down to part of the Alamogordo Bombing Range in the bleak and barren Jornada del Muerto (Journey of Death). The area had the advantage of being already in the possession of the government and it was flat and dry although almost constantly windy. The nearest inhabitant lived 12 miles away, the nearest town, Carrizozo, was 27 miles away. It was about 200 miles from Los Alamos.

The Jornada del Muerto derives its grim name from its barren, arid landscape. Old Spanish wagon trains headed north would be left to die in the desert if they ran into trouble since they could de- last week it was christened Project J. By actual pend on finding neither settlement nor water for 90 miles or so.

On August 14 Oppenheimer wired Groves in Washington that he thought there would be no problem in obtaining the land for their purposes but, concerned as usual about Jumbo, specified that “the northern part will be satisfactory to us provided the El Paso-Albuquerque line of the Santa Fe can carry a 200-ton load either from El Paso north or from Albuquerque south to the neighborhood of Carthage.”

The final decision was made on September 7, 1944 and arrangements were made at a meeting with the commander in chief of the Second Air Force for acquisition of an 18-by-24-mile section of the northwest corner of the bombing range.

Not long afterward, when it became necessary to choose a code name for the test, it was Oppenheimer who made the selection. Many people have tried to interpret the meaning of the name but Oppenheimer has never indicated what he had in mind when he chose Trinity. In any case, it did create some confusion at first.Bainbridge asked Oppenheimer for clarification in a memo written March 15, 1945:

“I would greatly appreciate it if the Trinity Project could be designated Project T. At present there are too many different designations. Muncy’s (Business) office calls it A; Mitchell’s (Procurement) office calls it Project T but ships things to S-45; and A portion of the Alamogordo Bombing Range was chosen as the site for the Trinity test. This section of the usage, people are talking of Project T, our passes are stamped T and I would like to see the project, for simplicity, called Project T rather than Project J. I do not believe this will bring any confusion with Building T or Site T.”

Nothing was simple in preparations for the test and the securing of maps of the test site was no exception. Lest Los Alamos appear involved, the job was handled by the Project’s security office which managed to avoid pinpointing the area of interest by ordering, through devious channels, all geodetic survey maps for New Mexico and southern California, all coastal charts for the United States, and most of the grazing service and county maps of New Mexico. There was considerable delay while the maps were collected and sorted.

Despite the many complicated steps taken to avoid any breach of security there were a few snafus. As soon as construction began on the test site it became necessary to have radio communication within the site so that radio-equipped cars could maintain contact with the guards and with people at the various parts of the area. Later, communication would be essential between the ground and the B-29s participating in the test. A request went out t. Washington for a special, exclusive wave 1ength for each operation so that they could not be monitored.

Months went by and at last the assignments came back. But alas, the short wave system for the ground was on the same wave length as a railroad freight yard in San Antonio, Texas; the ground to air system had the same frequency as the Voice of America.

“We could hear them (in San Antonio) doing their car shifting and I assume they could hear us,” Bainbridge reported later. “Anyone listening to the Voice of America from 6 a.m. on could also hear our conversations with the planes. ”

On the basis of a thorough Laboratory survey of proposed scientific measurements to be made at the test, justification for all construction and equipment requirements was sent in a detailed memo to Groves on October 14. On November 1 Groves wired Oppenheimer his approval of the necessary construction but asked that “the attention of key scientists not be diverted to this phase unnecessarily. ”

He needn’t have worried. By August the outlook for the implosion program had turned bleak indeed. The test preparations lost their priority and the Laboratory turned nearly all its attention toward overcoming the serious difficulties that were developing. Urgency in securing manpower for research and development on the problem was so great that all of Bainbridge’s group, except for a few men in Louis Fussell’s section X-2c, were forced to abandon their work on the test and concentrate on development of a workable detonating system and other top priority jobs lest there be no test at all.

Between August and February, however, Fussell’s section did manage to work on such preparations as acquiring and calibrating equipment, studying expected blast patterns, locating blast and earth shock instruments, and installing cables to determine electrical and weather characteristics, in addition to the design and construction of the test site Base Camp and the design and contract for Jumbo —about all the test program could demand with the plight of implosion so desperate.

Contracts were let early in November for construction of Trinity camp, based on plans drawn up by Major Stevens in October. The camp was completed in December and a small detachment of about 12 military police took up residence to guard the buildings and shelters while additional construction continued.

As the new year arrived, the implosion work began to show more promise and the Research Division under R. R. Wilson was asked to postpone even its highest priority experiments and turn its four groups, under Wilson, John Williams, John Manley, and Emilio Segre, to developing instruments for the test.

By February the Laboratory was mobilizing. Oppenheimer had long since been committed in Washington to a test in July and the deadline was fast approaching. In a conference at Los Alamos, attended by General Groves, it was decided then and there to freeze the implosion program and concentrate on one of several methods being investigated–lens implosion with a modulated nuclear initiator. The conference then outlined a detailed schedule for implosion work in the critical months ahead:

April 2: full scale lens mold delivered and ready for full scale casting.

April 15: full scale lens shot ready for testing and the timing of multi-point electrical detonation.

March 15-April 1.5: detonators come into routine production.

April 15: large scale production of lenses for engineering tests begin. (Lenses direct explosive’s shockwaves to suitable converging point.)

April 15-May 1: full scale test by magnetic method.

April 25: hemisphere shots ready.

May 15-June 15: full scale plutonium spheres fabricated and tested for degree of criticality.

June 4: fabrication of highest quality lenses for test underway .

July 4: sphere fabrication and assembly begin. By the following month the schedule had already been shifted to establish July 4 as the actual test date and that was only the beginning of the date juggling.

Overall direction of the implosion program was assigned early in March to a committee composed of Samuel K. Allison, Robert Bacher, George Kistiakowsky, C. C. Lauritsen, Capt. William Parsons and Hartley Rowe. For its job of riding herd on the program the committee was aptly named the Cowpuncher Committee and it was the Cowpunchers who had the responsibility for the intricate job of integrating all the efforts of Project Y, the arrival of critical material from Hanford and the activities at Trinity, site in order to meet the test deadline.