The British Mission

by Dennis C. Fakley

Originally published in LOS ALAMOS SCIENCE Winter/Spring 1983.

News of the discovery in early 1939 of neutron-induced fission in uranium immediately prompted ideas in the United Kingdom and elsewhere not only of a controlled fission chain reaction but also of an uncontrolled, explosive chain reaction. Although official British circles viewed with a high degree of skepticism the possible significance of uranium fission for military application, some research was initiated at British universities on the theoretical aspects of achieving an explosive reaction. Progress was slow, the initial results were discouraging, and, following the outbreak of World War II, the effort was reduced and resources were moved to more pressing and more promising defence projects. The turning point came in March 1940 with the inspired memorandum by O. R. Frisch and R. E. Peierls, then both of Birmingham University, in which they predicted that a reasonably small mass of pure uranium-235 would support a fast chain reaction and outlined a method by which uranium-235 might be assembled in a weapon.

The importance of the Frisch-Peierls memorandum was recognised with surprising rapidity, and a uranium subcommittee of the Committee for the Scientific Survey of Air Warfare was set up. This subcommittee, soon to assume an independent existence as the MAUD Committee, commissioned a series of theoretical and experimental research programmed at Liverpool, Birmingham, Cambridge, and Oxford universities and at Imperial Chemical Industries. By the end of 1940, nothing had disturbed the original prediction of Frisch and Peierls that a bomb was possible, the separation of uranium-235 had been shown to be industrially feasible, and a route for producing plutonium-239 as a potentially valuable bomb material had been identified.

The first official contact between American and British nuclear research following the outbreak of the war in Europe took place in the Fall of 1940 when Sir Henry Tizard, accompanied by Professor J. D. Cockcroft, led a mission to Washington. The MAUD Committee programme was described and was found to parallel the United States programme, although the latter was being conducted with somewhat less urgency. It was agreed that cooperation between the two countries would be mutually advantageous, and the necessary machinery was established. Even at this early stage the British increasingly recognised that, with their limited resources, they would have to look to the immense production capacity of America for the expensive development work; before long the MAUD Committee was discussing the possibility of shifting the main development work to America.

By the Spring of 1941, the MAUD Committee itself was convinced that a bomb was feasible, that the quantity of uranium-235 required was small, and that a practical method of producing uranium enriched in uranium-235 could be developed. It had also decided that there were no fundamental obstacles in the way of designing a uranium bomb. However, the possibility of a plutonium bomb had been pushed into the background partly because of doubts about feasibility and partly because large resources appeared to be needed for the development of a plutonium production route. The British were unaware of the work on plutonium already carried out by Professor E. O. Lawrence at Berkeley.

The MAUD Committee produced two reports on its work at the end of July 1941. These reports, "Use of Uranium for a Bomb" and "Use of Uranium as a Source of Power," were formally processed through the Ministry of Aircraft Production, the high-level Scientific Advisory Committee, and the Chiefs of Staff to Prime Minister Churchill, but, as a result of a great deal of unofficial lobbying, Churchill had made the decision that the bomb project should proceed before the official recommendations reached him. It was recognised that the project had to be set up on a more formal basis, and the Directorate of Tube Alloys-a title chosen as a cover name-was formed within the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research under the technical leadership of W. A. Akers, recruited from Imperial Chemical Industries, and the policy guidance of Sir John Anderson, Lord President of the Council.

Meanwhile, in the United States Dr. Vannevar Bush, head of the National Defense Research Committee, had asked the president of the National Academy of Sciences in April 1941 to appoint a committee of physicists to review the uranium problem. This committee, which was given copies of the MAUD reports, reached conclusions in November 1941 which were remarkably similar to those of the MAUD Committee, but it was less optimistic about the effectiveness of a uranium bomb, the time it would take to make one, and the costs. Surprisingly, despite the discoveries made at Berkeley, the committee did not refer to the possibility of a plutonium weapon. On the basis of the report of the National Academy of Sciences, President Roosevelt ordered an all-out development programme under the administration of the newly created Office of Scientific Research and Development and endorsed a complete exchange of information with Britain.

Although information exchange continued until the middle of 1942, the British were ambivalent about complete integration of the bomb project and expressed reservations which, with hindsight, make strange reading. By August 1942, when Sir John Anderson offered written proposals for cooperation beyond a mere information exchange, the American project had been transferred from the scientists to the U.S. Army under General L. R. Groves. Britain was probably no longer regarded by the Americans as being able to make any useful contribution, and the question of integration was deferred. Further, the imposition of a rigid security system by the U.S. Army led to such severe restrictions on the information exchange that the only real traffic related to the gaseous diffusion process for producing enriched uranium and to the use of heavy water as a reactor moderator.

The change in the United States' attitude toward cooperating with Britain came as a great shock to the British. Prime Minister Churchill took up the issue with President Roosevelt in early 1943 without any early sensible effect. Meanwhile, the British studied the implications of a wholly independent programme and reached what would now appear to be the self-evident conclusion that such a programme could not lead to results which could influence the outcome of the war in Europe.

A breath of fresh air blew over the scene when Bush, now director of the Office of Scientific Research and Development, and U.S. Secretary of War Henry Stimson visited London in July 1943. At a meeting with Churchill, a number of misunderstandings on both sides were satisfactorily resolved, and it was agreed that the British should draft an agreement defining the terms for future collaboration on the bomb project. The draft agreement included a statement of the necessity for the bomb project to be a completely joint effort, a pledge that neither country would use the bomb against the other, a further pledge that neither country would use the bomb against or disclose it to a third party without mutual consent, and recognition of the United States' right to limit whatever postwar commercial advantages of the project might accrue to Great Britain. A mission to Washington by Anderson reached agreement on provisions for establishment of a General Policy Committee and for renewal of information exchange. These provisions together with the points in the draft agreement were incorporated in the Quebec Agreement, which was signed by Roosevelt and Churchill on 19 August 1943.

There were still some minor hurdles to be surmounted before the Quebec Agreement could be implemented in detail, but they were overcome more rapidly than might have been expected by anyone who had experienced the difficult days in the first half of 1943. The increased cordiality of AngloAmerican relations was due almost entirely to personal relations built up at the working level. Of pre-eminent importance was the rapport established between General Groves and Professor James Chadwick, senior technical adviser to the British members of the Combined Policy Committee.

With the resumption of cooperation, the first task was an updating one. The British handed over a pile of reports on the progress of their work, and General Groves supplied a copy of the progress report he had just submitted to the President. The British were amazed by the progress made in America and staggered by the scale of the American effort: the estimate of the total project cost was already in excess of one thousand million dollars compared with the British expenditure in 1943 of only about half a million pounds. Chadwick was in no doubt that the first duty of the British was to assist the Americans with their project and abandon all ideas of a wartime project in England. He concluded that this would best be achieved by sending British scientists to work in the United States. Before the end of 1943, Chadwick, Peierls, and M. L. E. Oliphant had taken up indefinite residence in America. Chadwick was occupied mostly in Washington with diplomatic and administrative functions but spent some time in Los Alamos; Peierls worked initially on gaseous diffusion but later at Los Alamos; and Oliphant, with three colleagues, worked at Berkeley with Lawrence's electromagnetic team; a further two scientists were attached to Los Alamos.

The exodus of British scientists to America accelerated in the early months of 1944. However, those who joined the gaseous diffusion programme did not stay long, and all were withdrawn by the Fall of 1944. The British team which joined Lawrence at Berkeley built up rapidly to about 35 and was completely integrated into the American group; most stayed until the end of the war. The British team assembled at Los Alamos finally numbered 19, and, as at Berkeley, the scientists were assigned to existing groups in the Laboratory (although not to those groups concerned with the preparation of plutonium and its chemistry and metallurgy).

The first British scientists to go to Los Alamos were mainly nuclear physicists. They included Frisch, who led the AngloAmerican group that first demonstrated the critical mass of uranium-235, and E. Bretscher, who found a niche in the group already thinking about fusion weapons. As the team built up, most of the British scientists were allocated to work on implosion weapon problems and to bomb assembly in general. Implosion was considered before the British arrived at Los Alamos, but Dr. J. L. Tuck made a significant contribution with his suggestion of explosive lenses for the achievement of highly symmetrical implosions. During 1944 Dr. W. G. (now Lord) Penney was recruited to assist with the explosive side of the programme, as were Dr. W. G. Marley and two assistants. Eventually six British scientists (Bretscher. Frisch, P. B. Moon, Peierls, Penney, and G. Placzek) became the heads of joint groups and a seventh, Marley, became head of a section.

Further, two highly distinguished consultants were made available under British auspices, namely Professor Niels Bohr and Sir Geoffrey Taylor. Bohr's visits to Los Alamos were inspirational; Taylor was able to contribute significantly to the work on hydrodynamics.

There is no objective way of measuring the contribution made by the British to the Manhattan Project at Los Alamos and elsewhere. General Groves often acknowledged the importance of the early work in the United Kingdom and the substantial contribution made by her scientists in America, but he added that the United States could have got along without them. The British presence, though small, certainly had a beneficial effect on the morale of the Project. It served a function not otherwise available in that closed community-as a centre of second opinions by scientists whose reputations were generally admired.

Whatever the variations in the opinions of the British contributions to the Manhattan Project, there is no dispute that their participation benefited the British considerably. The course of the British nuclear programme in the postwar period would have been very different had it not been for the wartime collaboration. While United States law prohibited international cooperation on nuclear weapon design, the British were able to undertake a successful independent nuclear weapons programme, which, despite its small scale relative to that of the American programme, succeeded in elucidating all the essential principles of both fission and thermonuclear warheads and in producing an operational nuclear weapons capability. When the two countries came together again in 1958, following a critical amendment to the 1954 United States Atomic Energy Act, the developments in nuclear weapons technology over the previous eleven years were found to be remarkably similar.

It is also of interest to note the similarities between the wartime cooperation on the development of the first nuclear weapon and the cooperation which has ensued over the past 25 years under the 1958 U.S.-U.K. Agreement for Mutual Cooperation on the Uses of Atomic Energy for Mutual Defense Purposes (as Amended). It is possible to identify very many of the same strengths and weaknesses that were evident in the 1940s. Those who have been intimately connected with the collaboration on nuclear defence subscribe to the view that it works in the overall joint defence interests of the two countries.

The story of the choice of title for this committee bears retelling. When Denmark was occupied by the Germans, Niels Bohr sent a telegram to Frisch, who had worked in Bohr's Copenhagen laboratory, asking him at the end of the message to "tell Cockcroft and Maud Ray Kent." Maud Ray Kent was assumed to be a cryptic reference to radium or possibly uranium disintegration, and MAUD was chosen as a code name for the uranium committee. Only after the war was Maud Ray identified as a former governess to Bohr's children who was then living in the county of Kent.

About the Author

Assistant Chief Scientific Advisor (Nuclear), Ministry of Defence, London. The author is indebted to Professor Margaret Gowing, Official Historian of the United Kingdom Atomic Energy Authority, from whose book Britain and Atomic Energy 1939-1945 this outline history has been drawn and to Lord Penney who was kind enough to edit the text.

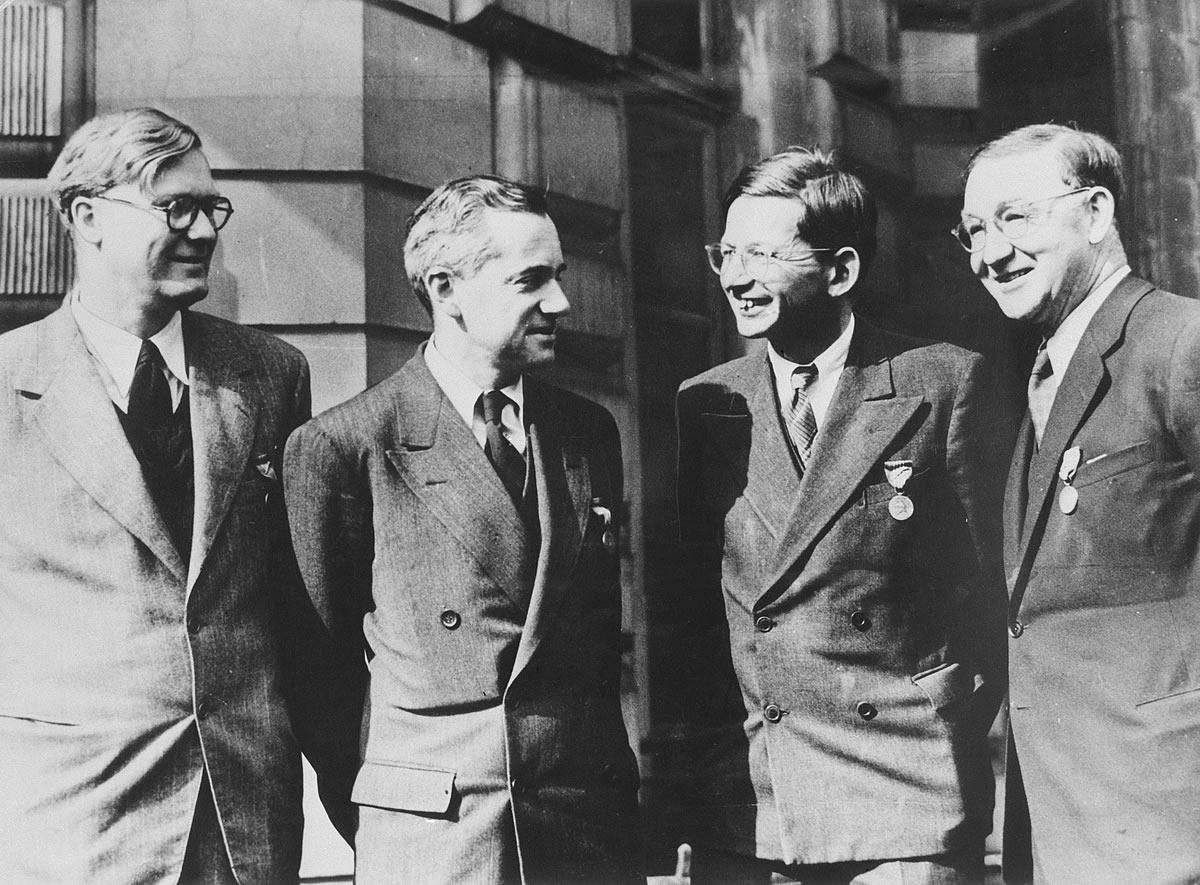

British Mission Members

- E. Bretscher

- B. Davison

- A. P. French

- O. R. Frisch

- K. Fuchs

- J. Hughes

- D. J. Littler

- W. G. Marley

- D. G. Marshall

- P. B. Moon

- R. E. Peierls

- W. G. Penney

- G. Placzek

- M. J. Poole

- J. Rotblat

- H. Sheard

- T. H. R. Skyrmes

- E. W. Titterton

- J. L. Tuck